Israeli-born, Tslil Tsemet describes herself as a painter, sculptor, and tattoo artist now based in Los Angeles. Certainly her work with tattoos serves her in good stead: one look at at Tsemet’s paintings and they will be indelibly tattooed on the heart and retina.

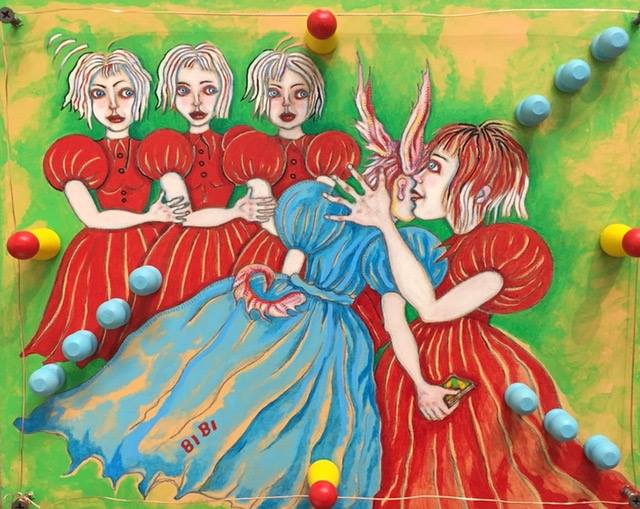

In Outliers, her solo show, which opened at The Neutra Gallery in Silver Lake last Saturday, the 29 year-old artist exhibits an enormous power, combining realistic portraits with surreal composition. Tsemet describes her work as a way to “examine the human species based upon the social and cultural values to which it is bound, and to those ideals we grasp in order to maintain our sanity.” The artist says that she both paints and sculpts using symmetrical composition, all the while blurring the line between what she refers to as “kitsch and sacrament.” Her desire, she notes, is to “sanctify so-called amoral” situations and modern life, using her work as a type of mythological illustration and allowing viewers to complete the story they see in her work. Tsemet has only been in the U.S. for two and a half years, but in that time the power of her work was almost immediately recognized; she had her work in a group show within months of her arrival.

There’s an assured, skilled hand behind her visual story telling. A number of her works, in vivid, vibrant oil, feature images that evoke a kind of spiritual ethos, cats that appear to have halos, father and baby in a pose similar to that of a Madonna and child. When asked what leads her to her particular subjects, the artist laughs. “It’s something I’ve been doing since kindergarten, I’m always doing naked people doing weird stuff.”

She began painting in oils at age thirteen, and developed her skills with precision. “I’m just interested in the human body and culture, and how our culture shapes us.”

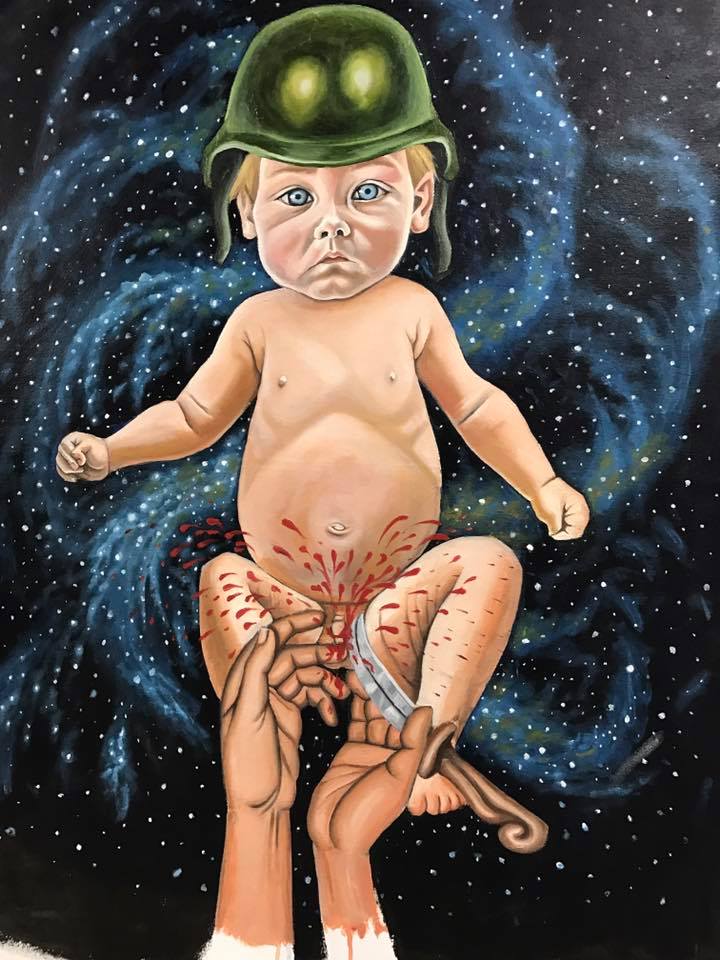

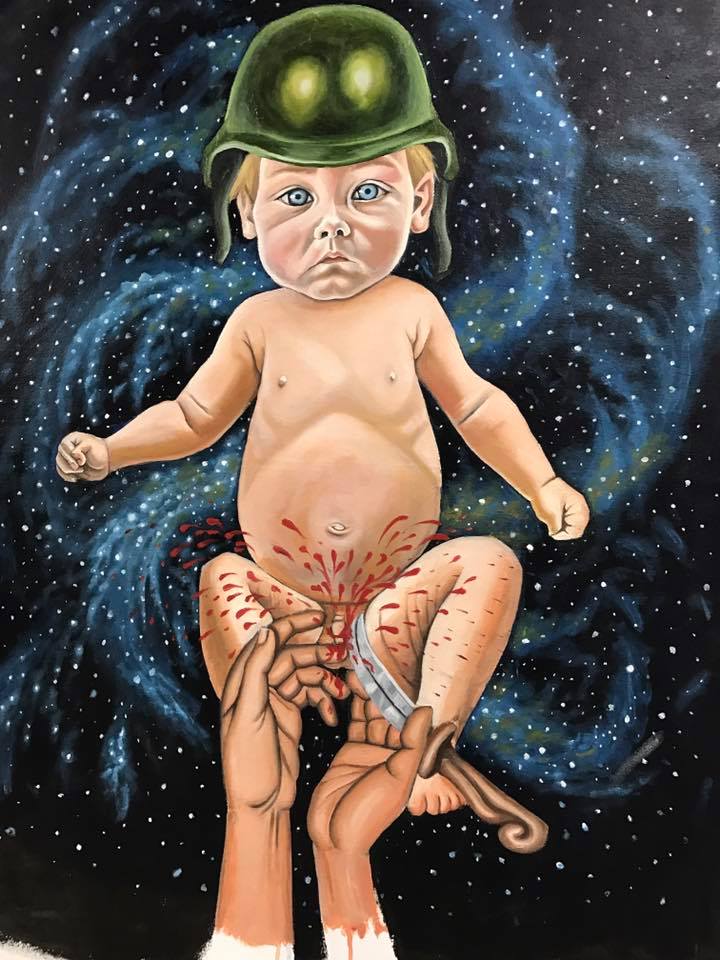

She used this interest as the basis for her “Circumcision in Space,” which details just that.

“I wanted to show how culturally we do things to human bodies, and to put that in a different context, here in space, to show how weird that is, really.”

In “Alex and Ronen,” her subject is more tethered to earth – man, child, and cat. “Alex Gross is my favorite painter. I love his work. I emailed him and told him how much I loved his work, and I’ve ended up being his assistant this year. It’s a wonderful experience, we don’t have the tools to develop technique in this way in Israel, it’s a different paradigm.” As a tribute, Tsemet created this portrait. “It’s Alex with his son, the cat I just put in there – I have a cat.” Behind the trio, palms bend inward and UFOs radiate.

This cat appears to have a halo – and the reason for this, and for that matter, the space ships, Tsemet shrugs off. “Images just jump in me, and I just paint, I don’t know what it means.”

A friend’s portrait formed the beginning of “Unspoken,” which also features a cat with a halo, this one even more vivid than in “Alex and Ronan.” But haloed cat and curious, looking-right-at-you subject aside, the most startling aspect of this painting is blood flowing as if from a spigot in the subject’s neck, straight into a wine glass. A voluptuous ruby red, the image is not gory, but rather intensely compelling, as is the starry sky and msyterious light in the background. “I was painting a dream to be a Bachelorette,” Tsemet explains. “It’s not the heart that is bleeding, it is the voice. It’s a mystery to me why I do stuff,” she demurs.

It hardly matters why: the result is assertive, mysterious, beautifully strange. Her work features breasts, cats, snakes, and babies; many of the pieces have an icon-like quality, not just because of the haloed cats, but because of the subject’s positioning, the light, the intensity of their gazes.

“It’s an intuitive process, it is coming from an idea. Ideas come to me, it’s not me creating them – they are trying to tell me something.”

“Tie the Animal” is the first painting the artist created in the U.S. “I was staying with a guy who had a tattoo shop, and one day a man came in, covered with tattoos but with a baby face. So there he is.” The baby-man is perched on a black velvet drape which partially covers a languid woman, breast exposed, body and face feminine and perfect — but her legs are men’s legs. Slightly strange, Pomeranian-like dogs surround them. “I have a feeling we are all engineered in some way, the dogs too,” Tsemet says.

In “The Widow,” Tsemet wanted to do something with “memorial tattoos” included. “I met this woman at a party. She was beautiful, in her 50s, and I wanted to paint her. Later, I realized her husband had died, so that was the connotation here, that she has a memorial tattoo of him.” The powerful, sorrowed blonde is bare breasted, with the memorial tattoo of a man’s face on her chest, and her upper body marked with rose tattoos. Behind her, the city of Los Angeles sprawls under a purple, nighttime sky. It is a perfect memorial to the city as well as to the man.

One of Tsemet’s favorite quotes is from Andre Breton “It is by the force of images that, in the course of time, real revolutions are made.” Indeed, her images are forceful enough to create a revolution, if only in the viewer’s mind.

“I want to tell people that part of me is feeling sorry I’m not a California artist, but I don’t really want to apologize for not being refined, for just getting the work out. People should look at what I do, and just unwrap a few layers in their brain,” she suggests.

Tsemet has no reason to apologize. Whatever nation – or universe – she is from, her images are electrifying, potent, powerful, and somehow prayerful, too.

- Genie Davis; photos: Genie Davis