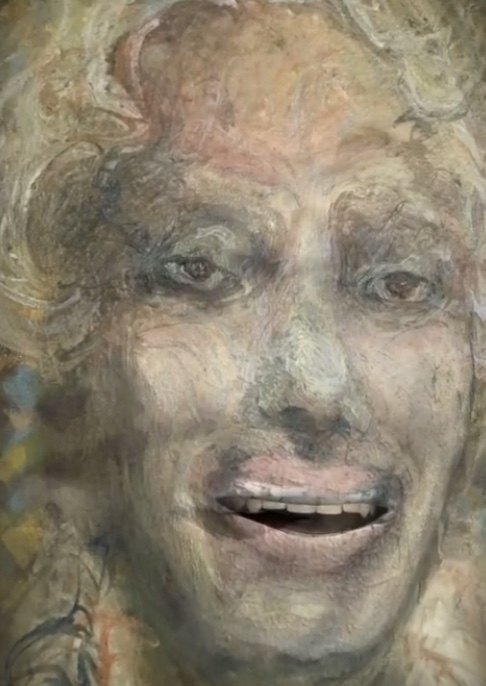

Artist Randi Matushevitz has created astonishing three recent bodies of work that are both emotionally resonant and plugged into the zeitgeist of today’s world.

The earliest series is Dystopian Lullaby. What is such a song? Does it soothe, does it rock the saddest soul into something astonishingly beautiful, hovering at the edge of hope? Does the strange melody somehow also seem distorted and off-balance, chaotic and inchoate? Matushevitz somehow manages to do all of these things with this series , one which is so poignant and real as to defy any routine categorization.

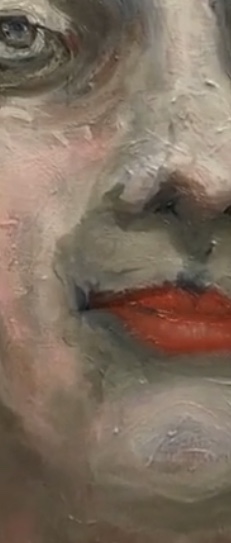

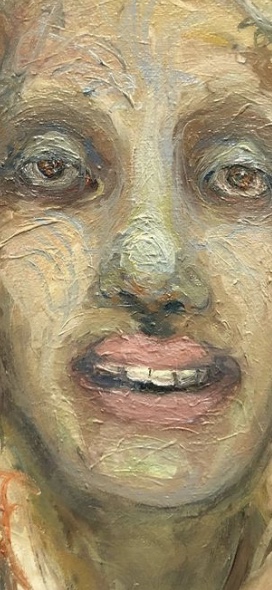

It is that poignancy perhaps that serves as a lullaby to these dystopian faces and settings. The people she creates, and even their elusive situations, are each sublimely real; they have lives we may not have been invited to visit before. For every element of distortion or horror at the state of their – and our – world – there is a sense of the rhythm of life, a brief impulse of comfort or longing. Created in oil on linen, the artist’s paintings feature backgrounds that are muted, often grey toned; the faces themselves reveal a palette of oblique and uncommon shades, while remaining entirely recognizable as “real.”

In images such as the artist’s “Cluster 4” (above), this dichotomy is richly evident. Matushevitz shapes an intimacy that compels the viewer into identifying with these dystopian inhabitants. In this work, a large, possibly disembodied figure appears to comfort a fully realized, frightened young girl. Behind her to one side, a shadowy outlined figure watches, with a benevolent if sorrowful expression. Two disembodied heads display alarm; one figure is partially reclining and seemingly viewing something entirely inward – perhaps this entire scene is a part of her memory. Like a film that makes the viewer long for a sequel, this work, too, aches for continuation and explanation, while still being wholly satisfying in its mystery.

There is a sense of family in each of the artist’s clusters, whether it is a “real” family, or characters that inhabit our own minds. Some of these characters reveal a sense of abject dread, but others seem at peace, resigned, ready to accept/embrace the dystopian world around them and possibly even shape an antidote for it.

Each image is both grounded in realism and yet layered in metaphorical abstractness. One can see the physical layers, which the artist creates by drawing, smudging, superimposing, and re-drawing or painting; and within those physical representations, within those impressive, passionate countenances, are layers of meaning and belief. If our own realities are made up of years of experience and knowledge, social interaction, and beliefs passed on from others and learned within ourselves, then so is the reality of these images.

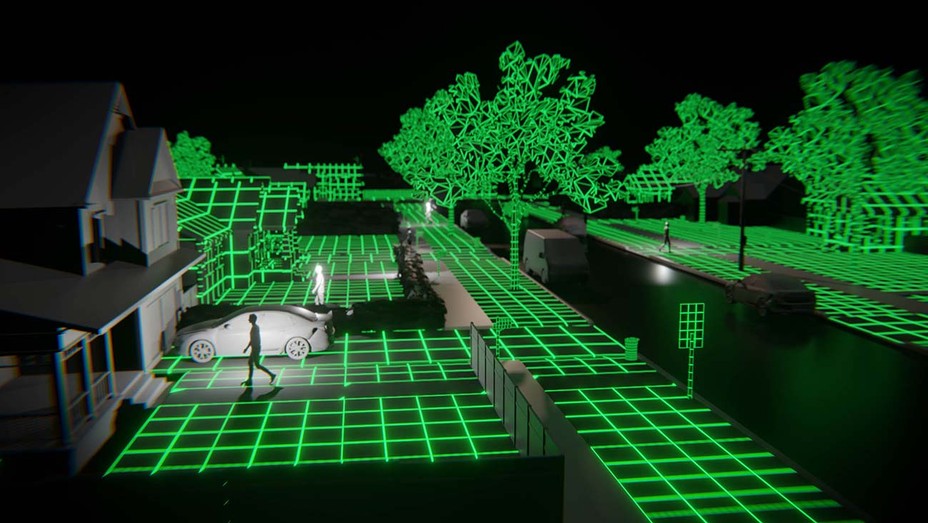

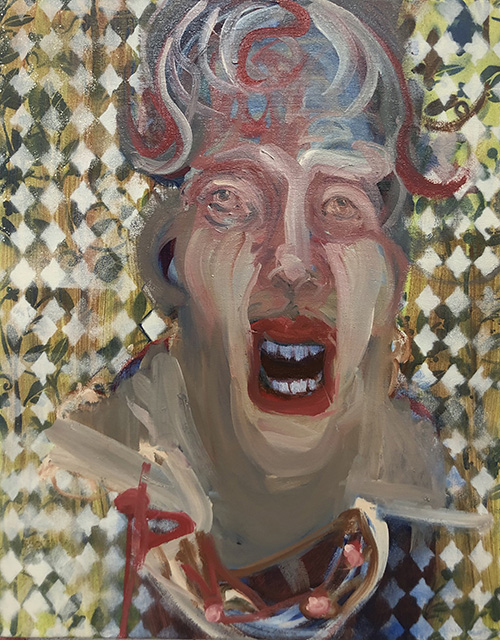

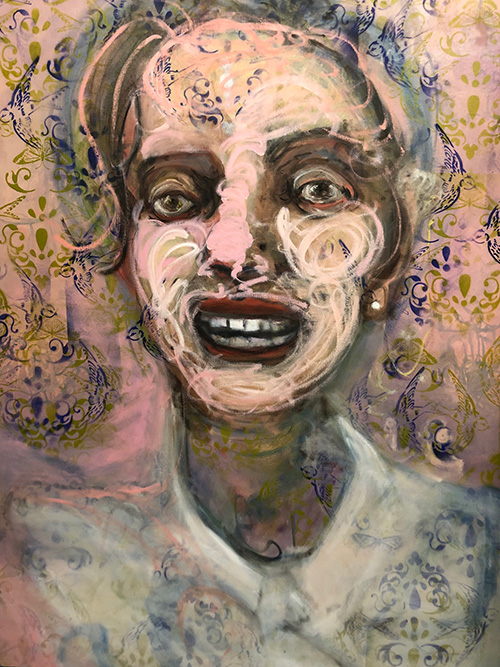

With Headspace and Headspace 3D (above), Matushevitz continues her nuanced exploration of the human condition and spirit, her works entering into increasingly complex spaces, mesmerizing and self-illuminative.

She often presents a conundrum of the spirit, in which she reveals the fears and indecisions, even the anger, that may lurk in each of us, but also a sense of exhilaration, of hope and connectivity, all filtered through her own affection for and exploration of human emotion. Just as her work itself is physically – and now, dimensionally – layered, so too is the meaning within it, packed with feeling and perceptive sensation.

Using what she describes as “emotional” portraiture, she captures an enormous amount of grace and resiliency in human expression, in both the oil on linen Headspace series, and its 3D and video iterations, Headspace 3D, the latter of which offers a vast expansion of fresh perceptions.

To create Headspace 3D Matushevitz initially used smartphone technology to animate her works, furthering her passionate deep dive into human expression, and to foster a sense of connectivity and community.

She began with simply animating the still images from her Headspace series, shaping a number of the images into Headspace 3-D. However, now they have grown into longer video explorations, revealing the subject of each image as a character with a breadth of emotions, as the artist explores meaning and non-meaning, and the true nature of understanding, and when it can occur. Matushevitz believes “We have an innate human ability that is in our DNA and in our sympathetic nervous system to understand. It goes beyond culture, gender and language.”

These new-media digital art works last from 6 to 20 seconds, and offer an intimate looking into portraits that have become uniquely alive.

As an artist, she reassures us that we may not be perfect constructs – in fact, we are each inherently flawed – but that does not make us any less valuable or worthy. She celebrates her people, however imperfect, revealing varied expressions, changing moods, and inviting the viewer into a full and immersive interaction with them in her 3D works.

It is a wonderful morphing of technology and art, very much of the moment and yet very much infused with a classic, intuitive intimacy associated with the art of portraiture. Nodding, laughing, turning, smiling, eyes close to filling with tears – these are the “living” manifestations of the moments her oil works portray.

Both in the more surreal-tinged 3D version, and in the original Headspace, much like ourselves, the people in her portraits are complex. They are both fully realized and in-progress, both expressing our outward personas and our inward dreams, fears, hopes, and unrevealed traumas.

Matushevitz’ “Adoration” may be the most benign image of the Headspace series. Peaceful, accepting, she has a half-smile and the most realistically-grounded skin tone.

“At the Wedding” (above, top) is another graceful image, one that nonetheless reveals watchfulness, resignation, subdued interest or acceptance; “Call Me Coiffed, I just left the Salon” (second image, above) offers a similarly recognizable and interested countenance, here, that familiar expression of feeling self-confident in one’s looks, in appraising one’s appearance in a passing window or mirror and feeling “well-done.”

“Chuckles, an ode to Matthew Barney” (above) is darker in tone, just as Barney’s works were often riven with allusions to defeat, failure or a sense of conflict.

It is perhaps with “I am She” (above) that all aspects of this series coalesces: this portrait appears to be of the Headspace universe’s creator, certainly of an every-woman. She feels, thinks, and is – everything. You see pleasure, sadness, hesitation, strength, all of these shifting across this image, although it remains physically still, not a 3D AR depiction – at least as yet.

Two interesting things to note about the wonderfully deep Headspace and Headspace 3D series: they are all of women, and in some way appear to be a kind of personal as well as collective self-portraiture; and the backgrounds are perfect and puzzling. Like a kind of patterned wallpaper or edgy Zoom background, these faces stand out against an environment that both clashes and offsets. All in all, that is not so dissimilar to how we experience the world today. We are who we are; the backgrounds we inhabit, whether IRL or virtual, do not empirically change us, although we may change them.

Headspace and Headspace 3D are both relatable and mind-bending, as all truly passionate art must be. These wonderfully immersive works make a perfect pairing with a visual “listen” to Matushevitz’ Dystopian Lullaby, a song for the senses, a melody of hope playing softly in a very discordant world.

- Genie Davis; photos provided by the artist