John Weston Compels Viewers to Enter “My Temple” by Genie Davis

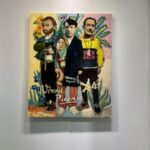

Artist John Weston’s solo exhibition My Temple, arriving at Ace Tiger Gallery March 1st, offers a vibrant display of explosive color as the Los Angeles-based artist creates new work that is both hard edged and soft of curves, mixing geometric and abstract patterns. True to his pop art roots, Weston’s work here vibrates with intense and hypnotic colors.

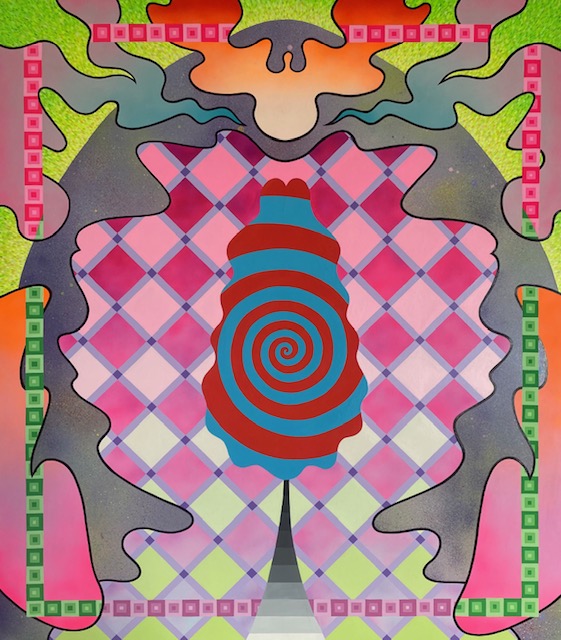

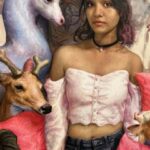

From the kaleidoscopic to the clearly sensual, a visual aesthetic that Weston has engaged in much of his work, My Temple clearly refers to the body as the artist’s – and our – personal temples, a place to reverently and fervently enjoy the physical in all its joyful permutations. Using a palette that includes hot pink, paler pinks, blues, greens, lavenders, and some orange, too, in a fresh, bright mix.

Weston frequently juxtaposes playful elements with an exploration of modern cultural norms, as in a 2019 show Pardon My French and Other Works at the Boston Court Theater in Pasadena, and in his transformation of everyday objects through the use of intense color and exaggerated form at his earlier Venice exhibition The Bedroom, which reimagined personal space. In My Temple, Weston is reimagining the body and our relationship to it.

With his lush rainbow palette and halrequin patterns, the viewer can clearly experience images of physical sexuality as well as images that appear culled from cosmic worlds and magic mushrooms. Riveting visually, Weston’s art is joyful, emphasizing our physicality with an exuberance and delight that viewers can’t help but experience for themselves. It’s as much fun as it is a lush and visionary experience.

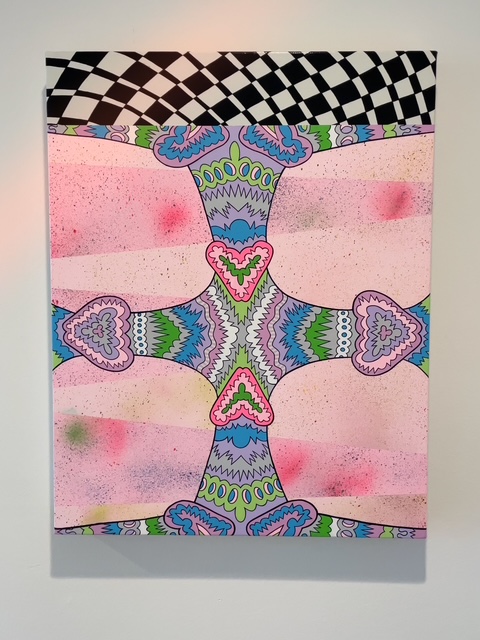

Never one to “Beat Around the Bush,” as Weston’s work, below, is titled, the artist’s work is cool, never cloying, and filled with motion, giving off an aura that pushes boundaries in the most delightful of ways.

If My Temple speaks to the idea of the body as a temple, it also speaks to the idea that Weston’s own personal temple is that of the spirit which inhabits us, integrating pop art with the current cultural zeitgeist. His conceptual approach asks viewers to consider, question, enjoy, and reimagine something we are all intimately familiar with, our bodies.

“Infinity,” above, truly takes on that kaleidscopic visual appeal while never letting go of Weston’s depiction of the body and it’s capability to be sexually playful. Using his signature bright palette and nearly psychedelic forms, Weston’s compositions are exciting not only as visual art, but as a commentary on contemporary life, and our view of ourselves and our bodies. The spiritual, the emotional, the physical are all intertwined, and the artist seems to posit that each aspect of our own bodies and lives is also intertwined with others in the world and the world itself.

The universality of Weston’s work is deeply appealing, as is his exploration of our physical and emotional presence in the world. The artist’s lighthearted and inclusive approach, along with his precise, bold, yet delicately lovely use of pattern and color in My Temple evokes the memory of that 1982 Marvin Gaye song “Sexual Healing,” the chorus of which goes “Makes me feel so fine/

Helps to relieve my mind/Sexual healing, baby, is good for me/Sexual healing is something that’s good for me.” Perhaps Weston was playing this tune when he was creating some of this work.

Weston’s new work isn’t all fun and frolic though. The images also reverberate with a touch of both the subversive and sublime. Mixing high art with pop culture aesthetics is no easy task, but the artist smoothly segues between the two, all the while challenging viewer boundaries both personal and visual, startling and jolting the eye away from the commonplace to create something the sparks and sparkles.

On view March 1st – April 7, 2025 at Ace Tiger Gallery at 24411 Hawthorne Blvd., Torrance. The opening reception is March 1, 4-6 p.m.

- Genie Davis; photos provided by the gallery