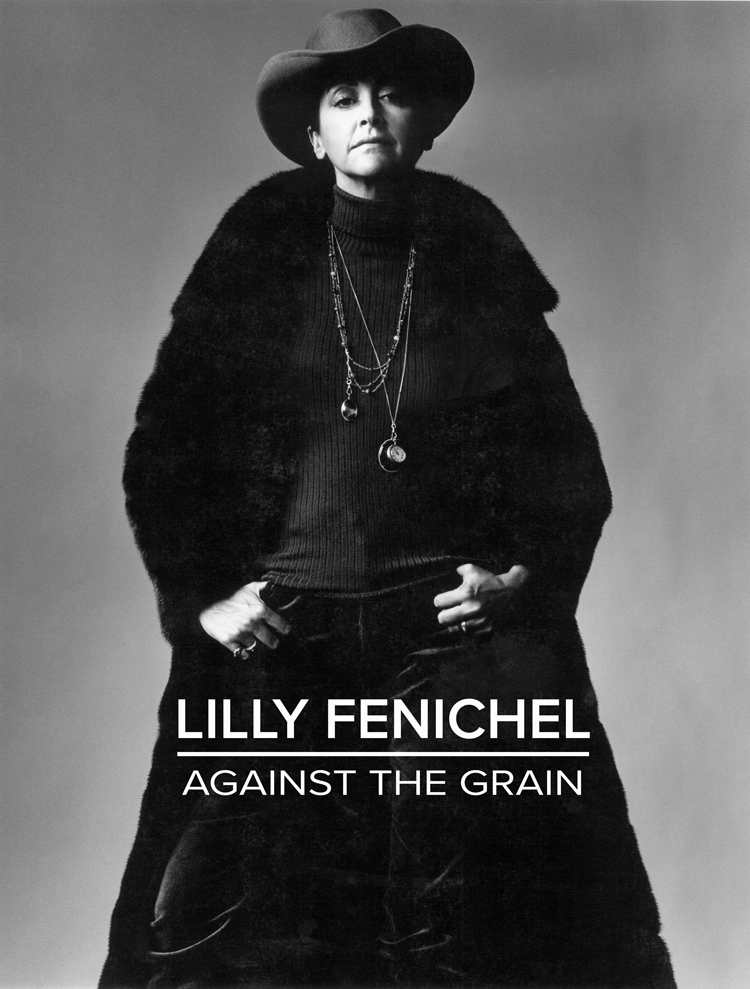

In the eponymously titled Lilly Fenichel: Against the Grain, artists, curators and critics Juri Koll and Peter Frank have composed a graceful book that traces a passionately committed and curious artist from 1949 until she passed in 2016, compiling her astonishing body of work in a fine retrospective.

To describe Fenichel as ahead of her time – in every decade – seems far too weak a phrase. In a wide-ranging artistic career that spanned seven decades, she worked in fresh forms and compelling shapes, always calling her work “non-objective” as opposed to abstract expressionism, geometric abstraction, or architectural.

She resisted limiting definiations and defied categorization, and in doing so, richly revealed just how far an artist can go without limits, whether self or societally imposed.

Trained in Vienna, an uncle brought her to Los Angeles to escape the Nazi regime prior to World War II. Studying and working in San Francisco, New York City, returning to LA, and moving to New Mexico, where she truly lived was in her art. Her shapes followed the decades, evolving with diverse palettes, moving through abstract rhythms and textures that slipped beyond the easily defined.

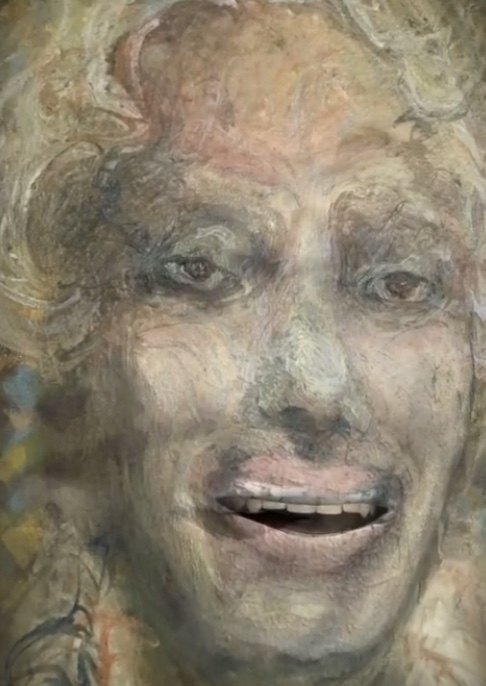

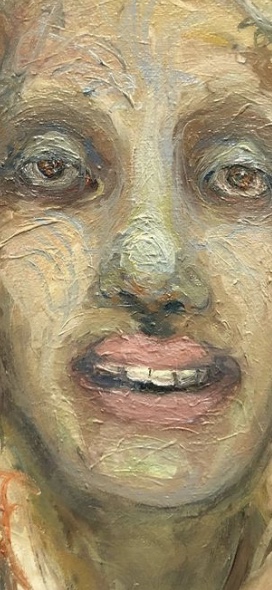

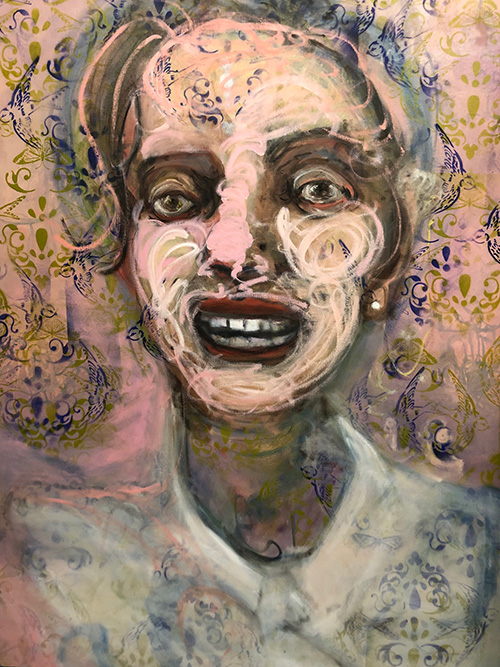

Dealing in abstracts of one sort or another, her powerful brush strokes and visceral approach were always astute. There is always a driving force seeming to race through her images, pulling the viewer within her aesthetic view of the world.

1950’s “Ochre, Red, and Blue” is an explosion of fire and shadow, a revolution of paint and purpose, both firework and campfire, filled with an inchoate sense of desire. Similar in style but electrically bright in lemon yellow, her “Untitled,” (1950) grabs the eye and doesn’t let go.

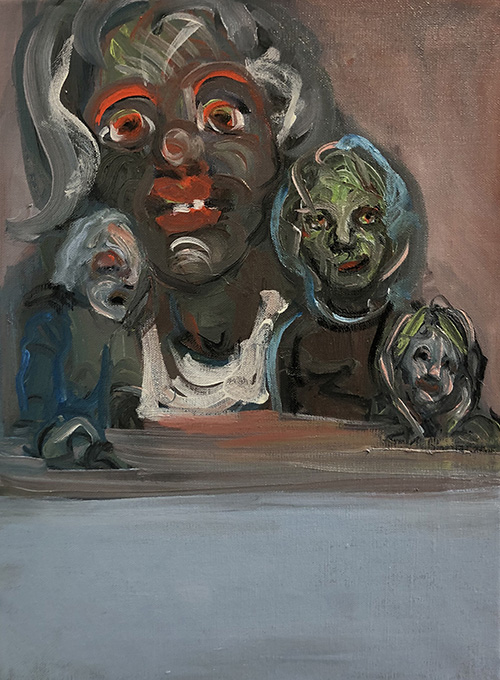

Other images from this period, such as “Circus” (1951) seem to evoke mysterious faces and shadowed forms within the main image. In this particular work, faces, flowers, and animals seem to lurk, ready to be born into the recognizable.

In 1960, created on yellowing newsprint, her “Nude Study (4)” is one of her few fully recognizable shapes – classic, faceless, and fine. Resting on her elbows, knees bent, the figure is a coil of unspent energy waiting to unfurl.

In so many of Fenichel’s work from this period, there is that same sense of energy, of a temporary entropy about to reformulate itself into immediate action. The sense of impending immediacy is one of the most unique aspects not just to this period, but throughout her entire body of work.

Moving into the gold, red, and blue of her 1962 “Geometric Color Study (6),” that same energy seethes below the surface of this mannered, careful unfurling of what could be flag-like bunting and podiums, or the surfaces of circus tents.

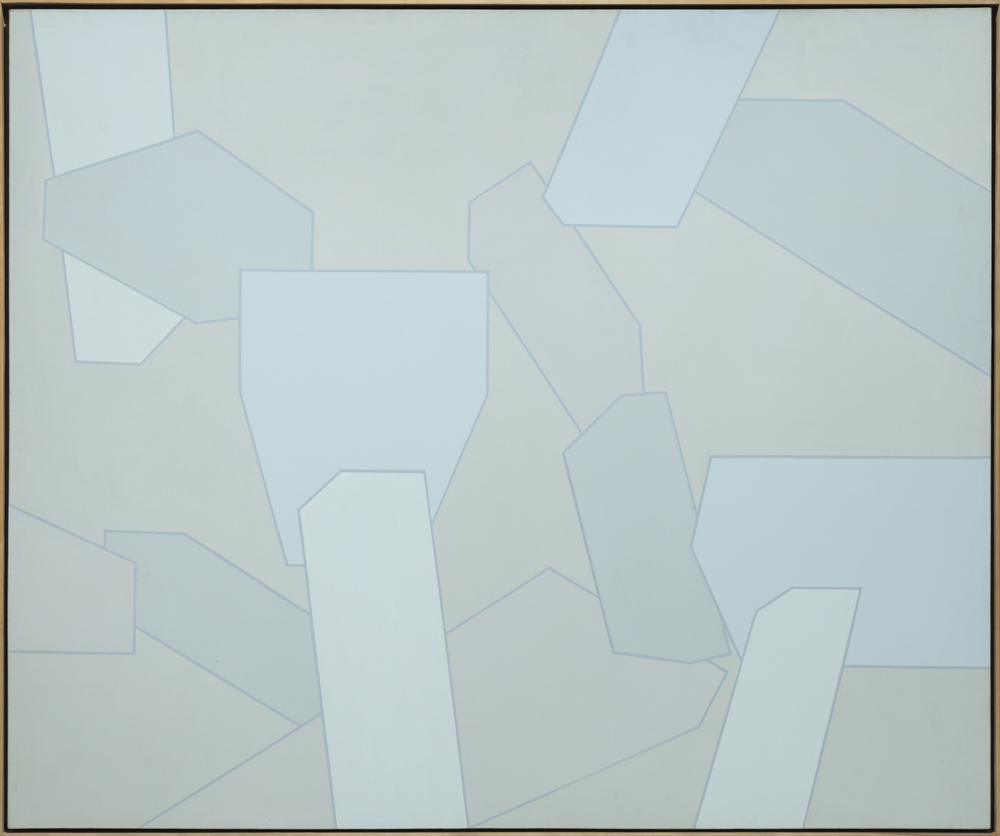

The cool, anvil-like patterns of her acrylic on canvas “Civil War” (1968) uses a unique combination of almost ethereal pastel coloring and a warrior like fierceness in its pattern. Fenichel seems to ask viewers if they see the hammers of change and rebuilding or weapons accumulated for wielding.

As this section ends, and elsewhere throughout the book, Koll and Frank offer quotes about Fenichel as an artist, and wonderfully evocative photographs of her. These serve to tie the book together as more than just a record of her artwork itself, but rather as a communication with the artist, a dialog in which her art speaks for her and to us.

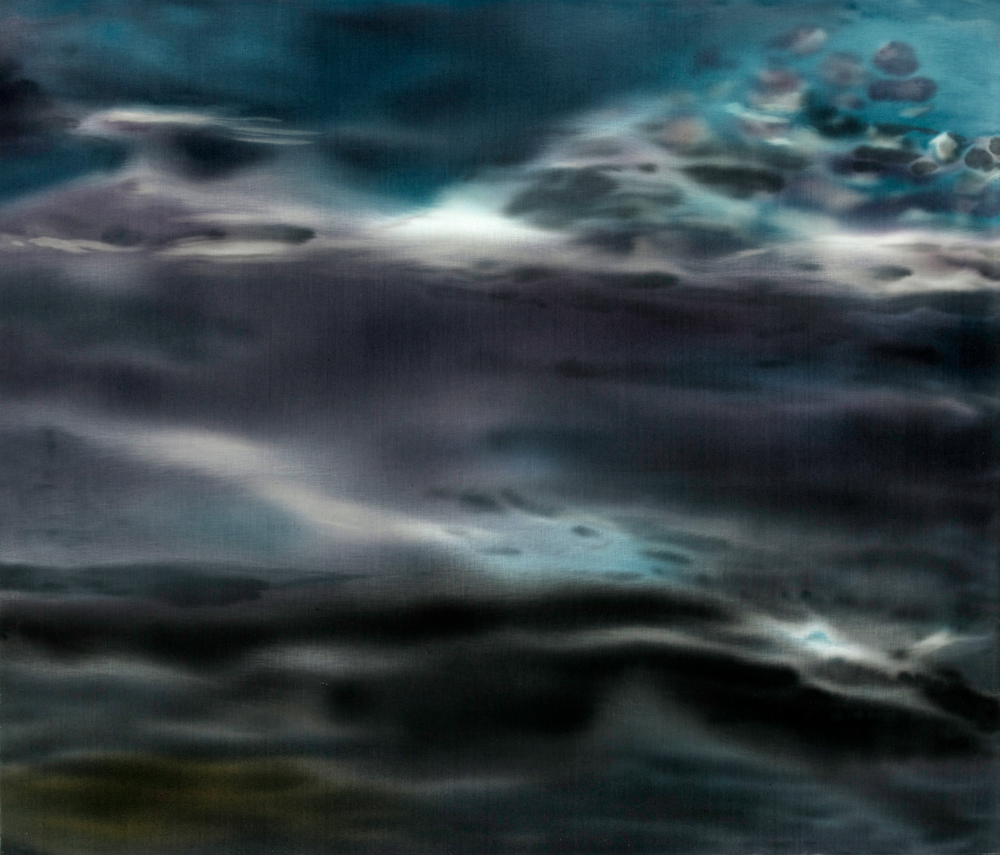

Moving into the 70s, Fenichel’s approach altered and her command became bolder. Here we see the vivid primary rainbow of “Blue Disc,” and the voluptuous ocean-like “Dark Blue/Black Sky,” acrylic on metal sheeting. The latter work is so deep and sensual that it encompasses the viewer, rippling in a dimensional outreach that feels as if its clouds brush the cheek.

Very different is the delicate, golden field of “Reeds/Bridge Hampton” and the layered, floral-like tangle “LA #10,” which subtly assimilates the flora and fauna and sunsets of the Southland in one image.

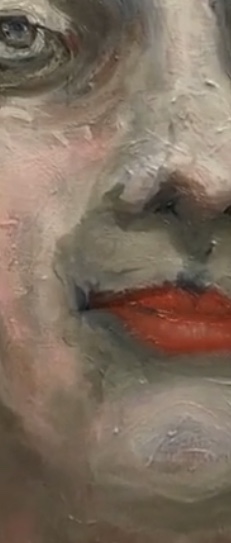

One of the most interesting elements of Fenichel’s work throughout her life was her very differentness. She did not hew to one medium or one “look,” beyond the non-objective. The other consistent feature of her vast body of work is a certain quality of the tactile, an almost physical emersion in which the artist commands the viewer to taste, touch, and experience what she depicts. And there is her sense of movement, a caught moment, that seems present in most of her images.

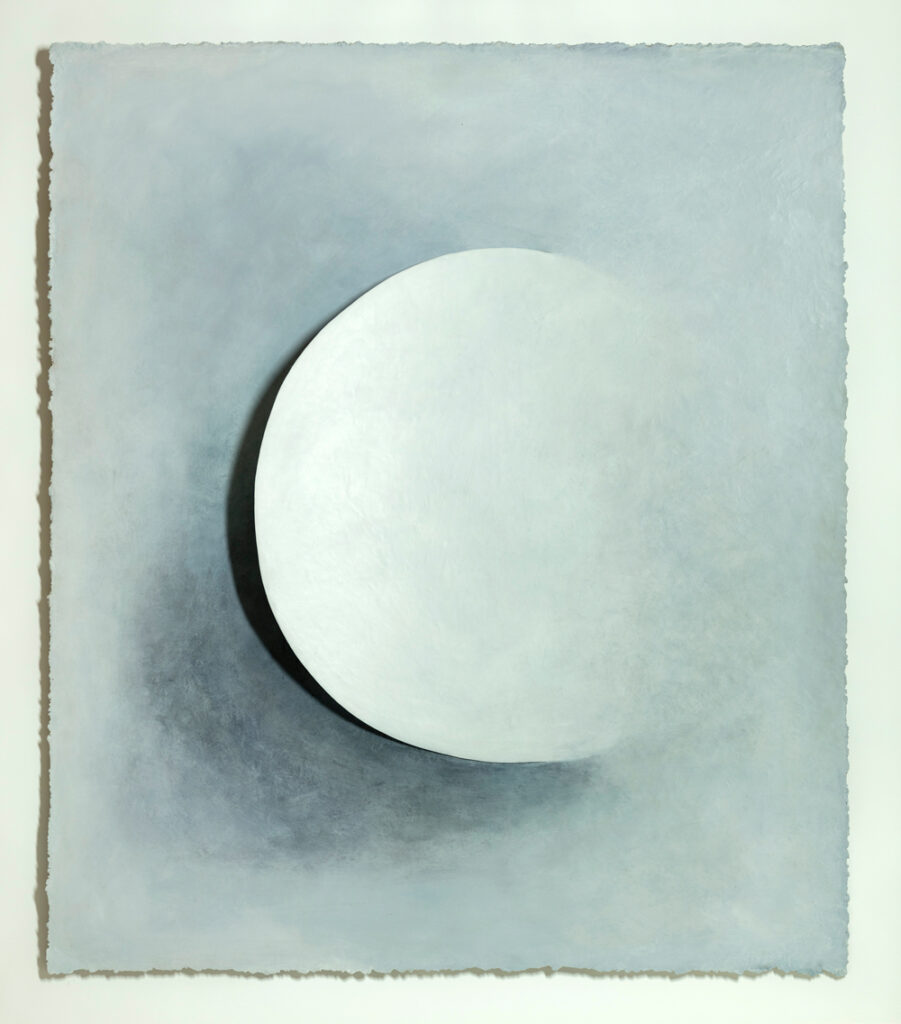

In the 80s, the artist moved into new mediums, including a deceptively clean, haunting work of oil on wood and fiberglass, “Taos Moon.” Invoking a sense of place – the plateaus of New Mexico – she also calls up the timeless, the eternal. Working in the same medium, her vivid yellow “Trikona” is both kite and bird.

From the same period, however, her graphite and colored pencil “Talpa Study 2” is another style altogether but shares an exuberance of line in its freeform monochromatic pattern.

Both visionary and symbolic – and prescient of today’s American political divide, something that’s rapidly becoming as iconic to this nation as apple pie – her oil on wood “Two Parts = A Whole” (1988) is a fiercely vibrant red and blue, both broken and perfect.

Moving forward in time, her work in the 90s, regardless of mediums, took on the quality of gemstones. Smoky quartz crystals come to mind with “Petroglyphs” (1992). Acrylic on processed paper, the painting appears to be a tumultuous but glowing collection of amber and black boulders. Also crystal-like are the bouquet jumble of “1991,” acrylic on Tyvek; and the shard-like image in oil and wax of “Emergence.” Also oil and wax, are the more defined but still quite crystalline shapes of “Take,” created in lapis lazuli blue.

Fenichel moved into an era of more sinuous abstract shapes in the 2000s, with some works that resemble dripping Japanese letters, such as “Untitled” (2007), evocative brush strokes of black and violet. Others, such as “Homage to Pei” are more dimensional, a deep dive into electric splashes of color and crisp form. There is a lushness of color that glows in many of her works from this period.

And in the 2010s, the artist went deeper, darker with images that resemble futuristic shapes, even planets, as in the oil on polypropylene “Work in Progress 10,” with its liquid-like texture. In the same period, “24C” also resembles a water form, a kind of soft grey shoreline against which a glowing near-tangerine landmass rests, while black streaks, curving and twining like serpents, seaweed, or oil spills move through both.

The book serves as a beautiful and thoughtful retrospective of Fenichel’s 65 years of art-making. Whether creating otherworldly sculptures in wood and fiberglass, painting on canvas, paper, or polypropylene, Fenichel made art as a personal statement, as a connection, as a creative lifeforce. Art was her nature, and she created it with as a wide and brilliant a scope as nature itself.

In a video interview with co-author Frank, Fenichel expressed her passion for her life’s work, without losing her sense of humor about it. She took her work quite seriously, but not herself. Art was pure to her, not to be sullied by commercialization, or the constraints of labeling her work as to specific genres or styles.

Always her own person, Fenichel’s art was uniquely fierce. Just as her work was filled with fluidity and motion, she moved through the world and her life as an artist, not categorized as a “female artist,” not allowing herself to be fit in any specific category. Rather, Fenichel was an explorer, whether of form or subject, a flame of joy that burned brightly through the world of art, and through the world itself. Koll and Frank have done a fine job of presenting her glow. The book is available at https://www.amazon.com/Lilly-Fenichel-Against-Juri-Koll/dp/B08WV2W7F1

- Genie Davis; photos courtesy of the book’s authors