The Fowler’s Fire Kinship Is Prescient and Important PST Art by Genie Davis

While conceptualized prior to our recent cataclysmic fires, Fire Kinship, now at UCLA Fowler is an incredibly pertinent exhibition that challenges the attitudes of fear and illegality around fire, presenting a cogent and quite honestly spiritual exhibition that proposes a return to lifesaving Native practices of fire.

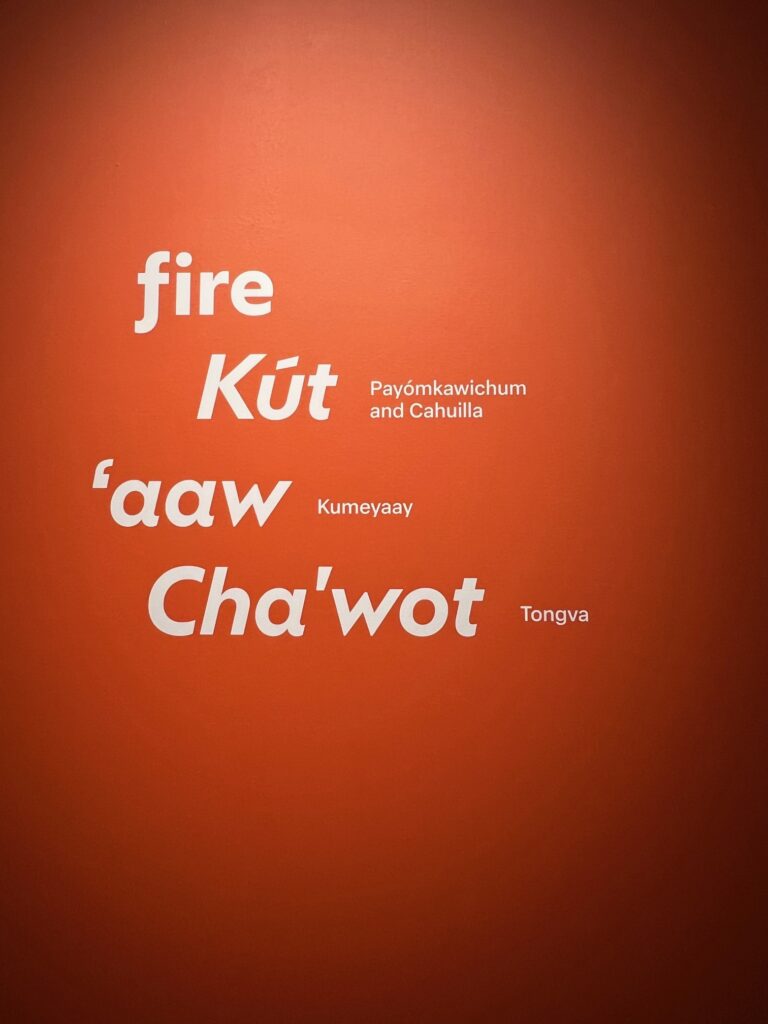

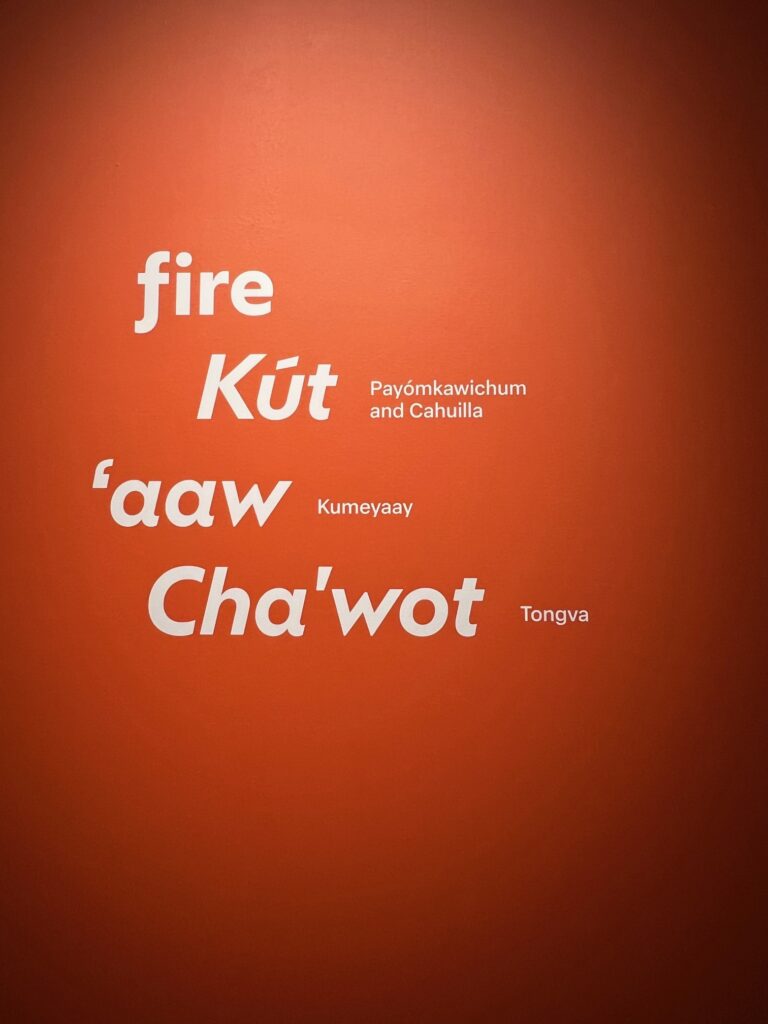

Hundreds of years of knowledge and expertise culled from the Tongva, Cahuilla, Luiseño, and Kumeyaay peoples, is presented in installations, poetry, craftwork, and paintings in the exhibitionn. Works highlight Native understanding of fire as a vital aspect of land stewardship, community well-being, and tribal sovereignty.

The exhibition presents a living history of communities from the past and present as told through a variety of mediums. It introduces the purpose of fire as a generative force and part of a sustainable future as an “elemental relative” creating a cycle of beginnings for all living things.

Among the works on display are beautiful items on loan from Native communities including baskets, ollas, rabbit sticks, bark skirts, and canoes. Each of these objects represents salient facts: fire tempers and hardens clay vessels used for cooking and storing food, helps to cultivate plant materials utilized to create baskets, blankets, capes, and skirts, thins out patches of juncus to allow new growth, softens tar used to make canoes seaworthy.Summer Paa’ila Herrera (Payómkawichum) has created two pieces for Fire Kinship. She displays a lovely ceramic vessel made from tó’xat (clay) sourced on traditional Luiseño lands, gathered with the help of her father, and processed at their home at Pechanga. Also on exhibit is a traditional skirt made from burned cottonwood bark that the artist herself has worn and will continue to wear in ceremonial settings.

Collaborating with key Native commuinty leaders, Fire Kinship explores a radical rethinking of our relationship with all the elements of the earth, our home: fire, water, land and air. Native ecological techniques hold vast and essential knowledge for our future survival. Co-curator Daisy Ocampo Diaz relates that “Southern California Native communities are bringing fire practices back from dormancy…Colonization, both past and present, disrupted a cycle that honored fire at the center and caused earth-wrenching ramifications. Native communities have been holding on to these gentle burns despite California’s ravaging by flames. We are all part of this story, and it is a time for listening and (un)learning.”

Along with the presentation of beautiful, hand-made objects for use and wear, the exhibition includes some vibrant and truly immersive installations, with several focusing on the vivid colors and growth of our California poppy.

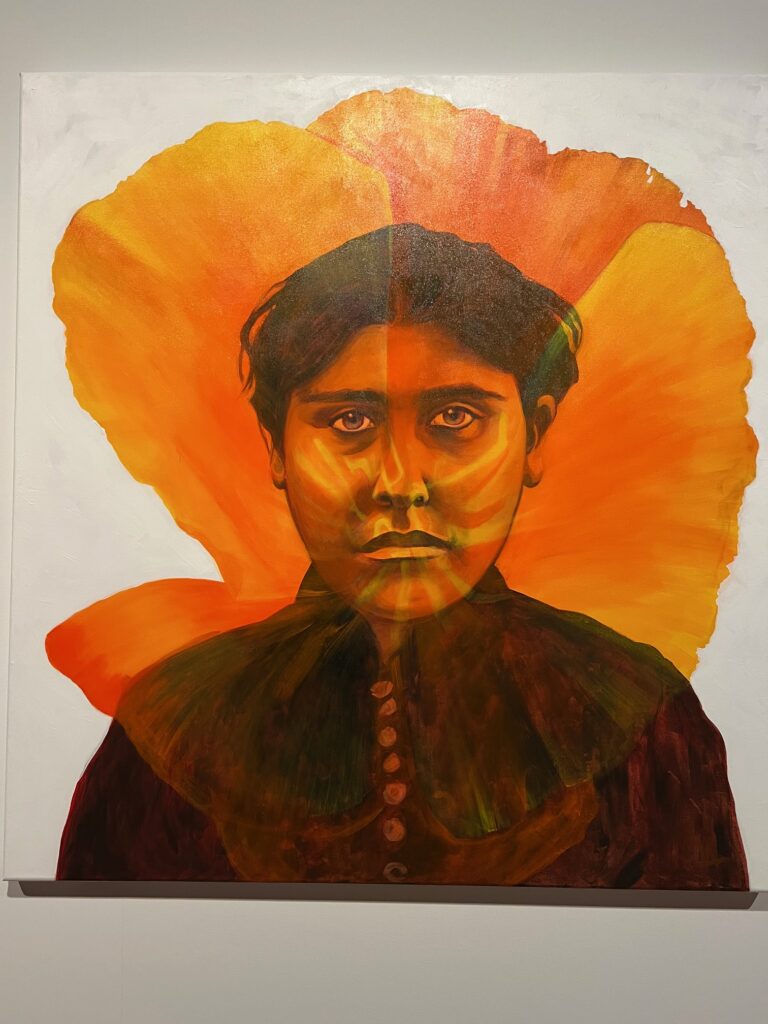

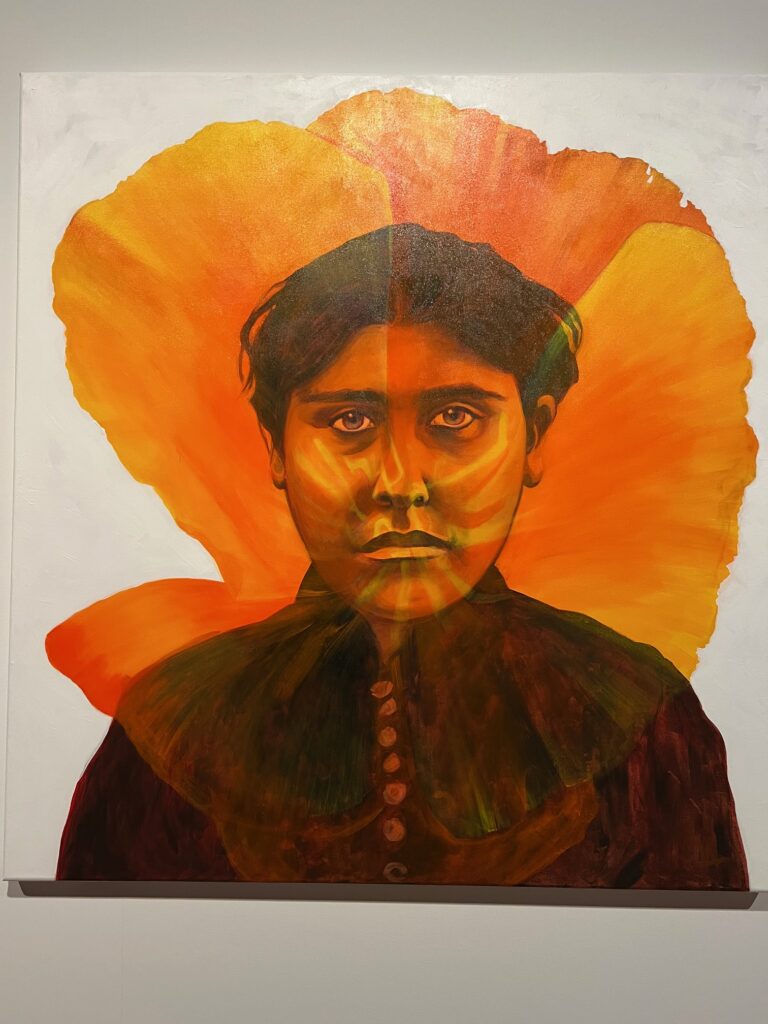

Weshoyot Alvitre creates a poppy-splashed portrait series exploring the multilayered histories of several women from her tribal community who fought for their people’s rights: Narcissa Rosemeye, a Tongva language keeper; Modesta Avila, who protested the development of the Santa Fe Railroad on her family’s land and became the first convicted felon in the state of California; Espiritu Leonis, who protected her ancestral homelands by using the United States legal system in a 15-year case. The portraits are powerful, evocative, and beautifully alive, apt tributes to brave and resourceful Native women.

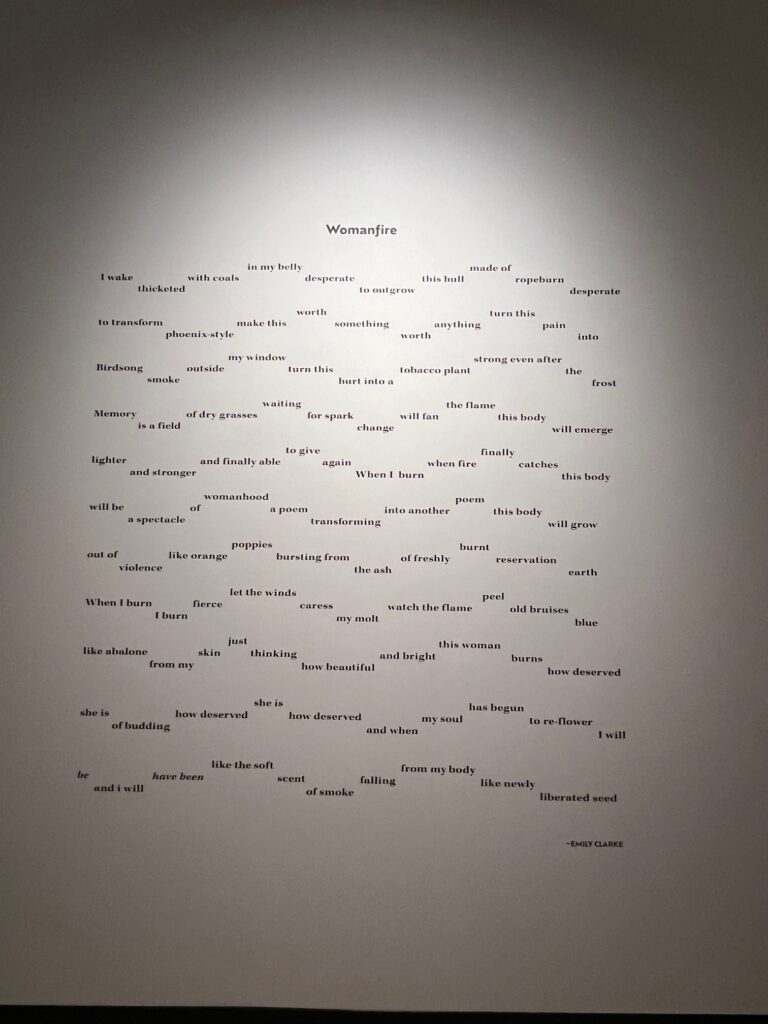

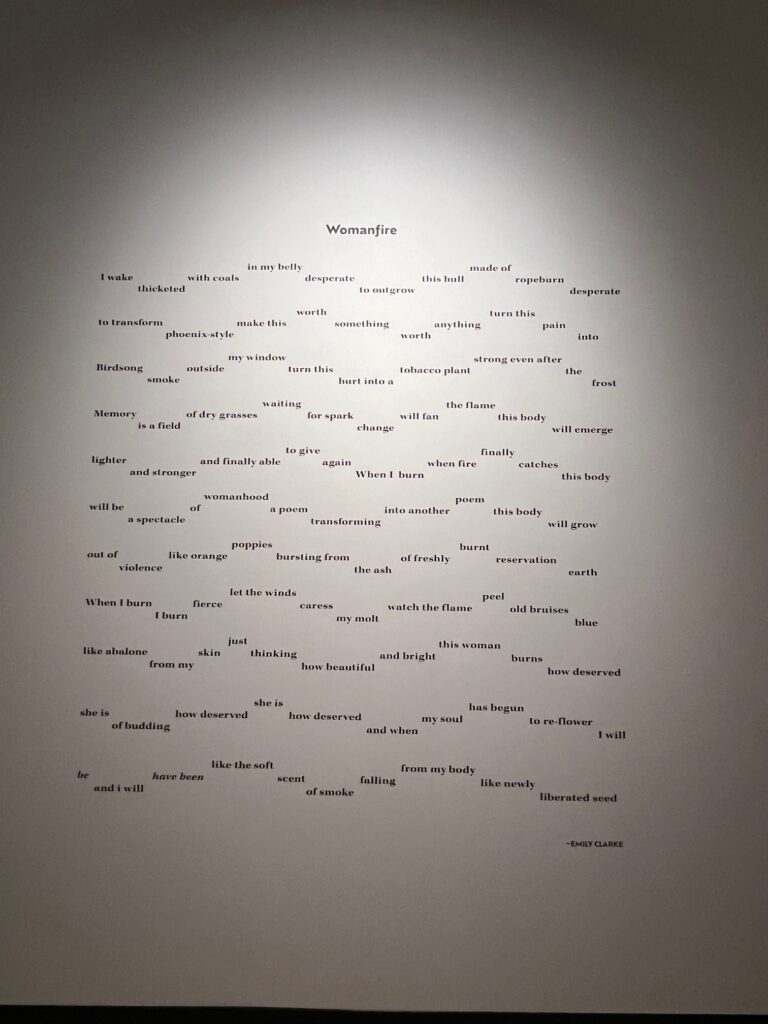

Alvitre’s portraits face a wall installation of a new work from poet Emily Clarke (Cahuilla Band of Indians), Womanfire. The poetry is moving and rich, written in electrocardiogram-esque lines that imitate a Cahuilla basket pattern believed to represent the mountains and valleys in Cahuilla homelands. The gloriously strong writing reflects on the fact that Native women are disproportionately at risk of experiencing violence. She intertwines this fact with another: their survival of abuse and trauma can be compared to a cultural burning, one which encourages renewal, regrowth, and abundance.

Also poetic is a multimedia installation, “The Heart is Fire.” The installation includes video, birdsong audio, and natural materials and was created by Gerald Clarke Jr. (Cahuilla Band of Indians). The piece is inspired by the Cahuilla creation story, a book about the Cahuilla by Deborarh Dozier, and traditional uses of fire. It also introduces and reflects upon the use of contemporary burns during all-night funerary ceremonies and bird-singing events within Cahuilla communities.

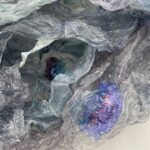

Admittedly my favorite installation is a room sized work by Leah Mata Fragua (yak titYu titYu yak tiłhini, Northern Chumash). The artist reclaims the narrative that the land and its people are intertwined through the use of a multitude of sculptural paper, dyed with poppies, and representing the flowers themselves. There is a small couch in the room on which one can lean back and look at the poppies everywhere in the room, their vast ability to thrive, to astonish, to regrow and regenerate. The installation looks to land stewardship practices that have shaped the region’s landscapes, long before European colonizers arrived in this country. It is a delicate and honestly divine work, uplifting and yet tragic in its fragility, mirroring ,in a way, the fragility of humankind itself, and our ability to regrow and accept alterations to our landscape.

As astonishingly lovely as it is, the work is meant to be temporary. The artist will return its materials to the earth through fire, symbolizing the cyclical nature of yak yak titYu titYu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash knowledge. The fragile beauty and its ephemeral nature speaks not only to that of flowers and all natural things, but to the spirit, its preservation, its loss.

Another highlight is the instalaltion “Sand Acknowledgment” by Lazaro Arvizu (Gabrieleno/Nahua) that reflects traditional and ephemeral sand-painting practices. Arvizu illustrates the connections between the land, humans, the sun, the stars, and animals. Like the installaton of Fragua’s poppies, this work too will return to the earth at the end of the exhibition.

Arvizu will also be present in the gallery for conversations, facilitated meditations, and art-making activities related to her installation throughout the exhibition time period.

Fire Kinship also includes photographs and archival documents that tell the story of colonization, including journal entries from Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, whose company of Spanish settlers was the first party of non-Indians to set foot in what is now Southern California in 1542.

I would like to note that even more powerful than this graceful and knowledge-filled exhibition itself is the acknowledgement of the fact that Native communities in Southern California continue to face institutional barriers to bringing life and land-saving fire back to the the land. Reintroducing and strengthening Native fire practices requires commitment and accountability from agencies with current jurisdiction over tribal territories.

With this in mind, there is also a section of the exhibition featuring videos and images of fire practitioners, such as Marlene’ Dusek and other members of the Indigenous Women-In-Fire Training Exchange (TREX), sharing knowledge and participating in controlled burns. The Fowler’s press materials explain that “They make a case for members of Native communities to become state-certified Burn Bosses, responsible for planning fires, obtaining permits, implementing burn plans, monitoring fire effects, and maintaining prescriptive requirements. This has been an option in California since 2018, but to date, only one Native person in Southern California is a certified Burn Boss—Fire Kinship collaborator Wesley Ruise Jr.”

The exhibition is on view through July 13th – and especially given its real-life context as well as its wisdom and beauty, is a must-see. The Fowler Museum is located on the UCLA campus in Westwood, Calif.

It was organized by the Fowler Museum at UCLA and curated by Daisy Ocampo Diaz (Caxcan), assistant professor of history at California State University, San Bernardino (CSUSB); Michael Chavez (Tongva), former Fowler archaeological collections manager and NAGPRA project manager; and Lina Tejeda (Pomo) M.A. in history at CSUSB.

The exhibition is part of the nation’s largest art event, Getty’s PST ART: Art & Science Collide, and as such is one of the most meaningful and important in this iteration of PST ART.

- Genie Davis; photos by Genie Davis