At the Main Theater in Santa Clarita last month, artist Aazam Irilian presented a sensitive, impactful, and beautiful exploration of memory – and how fragile and meaningful our memories are in human life. Preserved Memories, her exhibition on the impact and progression of dementia, packed a powerful and poignant punch.

Consisting of five different major sections, Irilian’s work depicted personal and moving stories through a varied and immersive mix of mediums including sculptural assemblages and recorded stories. The exhibition also allowed space for visitors to write their own stories.

In the exhibition’s “Traditional Bodies,” a series of delicately rendered graphite drawings of brain cells, neurons and more are intricately revealed in stylized bodies on panels of white fabric.

A series of “Shredded Mind Panels,” created on canvas panels in richly colored red darkening to shades of brick, are used to depict the loss of memory. Holes in the panels represent the losses caused by dementia, as the canvases gradually turn into trailing, shredded surfaces.

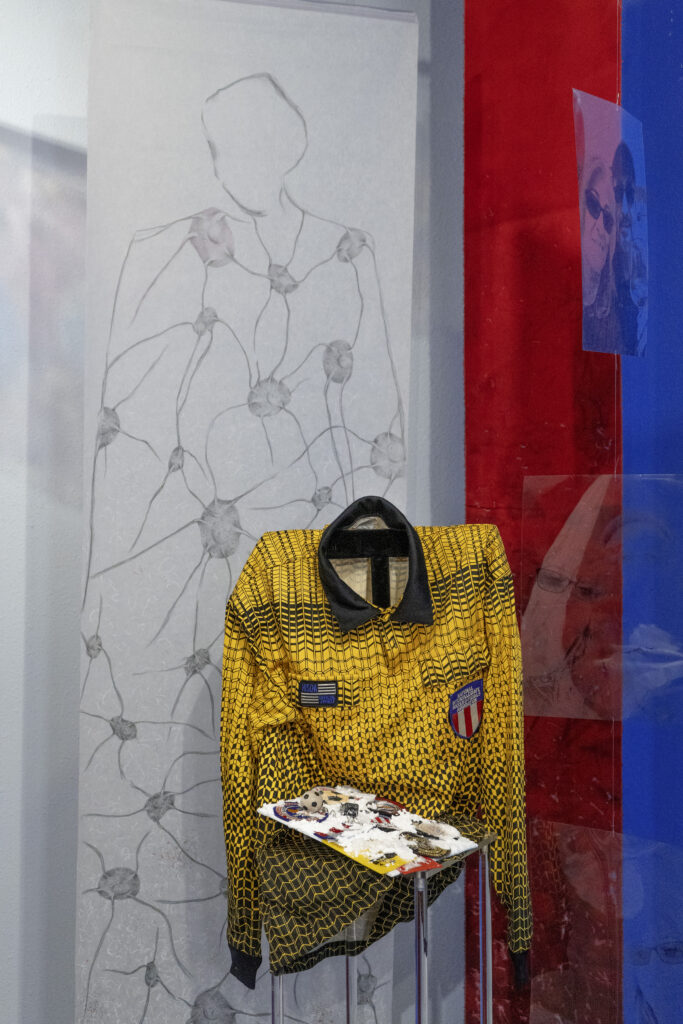

Perhaps the most compelling element of the exhibition is the titular “Preserved Memories,” a series of sculptural assemblages created out of personal memorabilia and preserved in salt. Stories that relate to the sculptures are a part of the recorded messages and memories section of the show. The sculptures themselves are haunting and nuanced, puzzle pieces of a life, the meaning of each piece transitory.

The haunting sculptural assemblages are, Irilian says, the focal points of the exhibition, which is not surprising to hear given the intensity and complexity of these works. Each represents an individual’s stories. According to the artist, “The soccer player piece is made of my husband’s soccer gears as referee. He was an engineer and played soccer most of his life. He also had coached and was a referee for the last 20 plus years.”

Using a variety of salts and mineral solutions as a part of her creative process, Irilian created a layered depth to her sculptures which arose from painted work. “The textures you see on my paintings are results of interaction of mineral solutions with paint. With each series, I aim to push the use of mineral solutions to a different level. With this installation, I pushed myself to see how I can grow and use these crystals off the canvas, onto the objects.” She notes that “Salt has been used as a preserving agent over the ages. The point here was to use the salt as the metaphor—preserving memories that are fading away.”

And in the series “Fading Family Portraits,” photographs printed on Duralar clear paper depict families of different cultural backgrounds who have suffered from dementia, revealing that the disease is not discriminatory and can strike any family, regardless of heritage. In a succession of photos, each face appears less and less clear, with ghostlike faces gradually fading away altogether, emblematic of how recognizability fades for a person with Alzheimer’s.

Each of these exhibition sections are evocative and sensorial, creating in the viewer a sensation of loss and legacy, of both the joy and pain of remembering.

Irilian does not approach her subject uninformed. She was both wife and caregiver to a husband who suffered from dementia. Dealing with both her own and his sense of loss keenly, her work movingly stresses that despite fading memory and a loss of identity itself, the afflicted person will not fade from our own memories and hearts.

The exhibition is important not just to Irilian personally but to so many, with the strong possibility that by the year 2050, those 65 and older suffering from Alzheimer’s are estimated to reach the daunting number of 12.7 million affected individuals.

This is not Irilian’s first installation work. The artist created the exhibition “Dare to be a Woman” at CSUN in 2004, and “Stoning” in 2005. Both employed a variety of mediums in their representation of violence against women in Iran. In “Stoning,” part of a 5-woman exhibition, she used a plaster cast of her daughter’s body. In short, the artist is no stranger to using the personal to represent a more universal situation.

Preserved Memories very much expands on these and other past work of the artist, who terms herself “a curious person…[who] wants to learn as much as possible, and that includes learning about how things are made and work. I feel installation is just another way, another tool in my bag of tricks that I can use to bring an idea into form.” Irilian never prefers one medium over another, she says. “It is about what medium can help me to bring in to form the idea or the concept.”

She strives to tell a story through her art, as well as to “create an experience or evoke an emotion. I want the viewer to bring her/his experience into each piece and find or form his own story viewing the work.” With Preserved Memories, she relates that most of all, she wanted to bring attention to the devastating disease, and impress a human face upon it, while “communicating the fact that the person we love is still there.”

Irilian plans to grow Preserved Memories as an exhibition, expanding the sculptural assemblages representing shared stories, and presenting the show in as many different venues as possible with her goal to improve understanding of Alzheimer’s and elevate compassion for both those suffering from the disease, as well as for those caring for their loved ones.

To do so, she’s seeking more stories on which to base her assemblages. “The stories told by loved ones are the most meaningful part of this project. I collected these stories through a Google number I set up (661) 347-6849. People can call and leave their stories without having to talk to anyone.” She encourages others now to call and share, and explains “The purpose of the stories is to honor and remember a memory that brings joy to the heart and a smile to the face. Like the woman who at the end of her life, opened her eyes and told her daughter, ‘I love you.”’Or my husband, who [when] seeing soccer games on TV, would light up… it was something he could still remember.”

The more people share their stories, she says, the more such projects are seen, and the more attention that will be brought to the disease. “And maybe at some point, we find a cure for it,” she says. “To put a human face on this disease, honor memory of our loved ones…I can only do that by people being courageous and willing to share their stories.”

Following this tenet, Irilian has created a brave exhibition that reveals the face of the disease and its impact on those afflicted as well as on the people who love them. Viewers will feel the pain, but also life – and memory’s – impactful, aching, beauty.

- Genie Davis; photos provided by the artist and by LA Art Documents