OBSERVATION(S): STEVE SHRIVER AND CANDICE GAWNE

Guest Post by Peter Frank

Above: Peter Frank with Steve Shriver

Art is not just about seeing, it is about observing. Whether the artist’s eye is turned outward towards the world or inward towards the self, the art arises from the phenomena, glorious and mundane, that present themselves to attentive vision. Even non-objective or conceptual art begins with a note of some kind, visual or not, that triggers passage down an experiential and expressive path. It may seem obvious that more traditionally pictorial art results from, even seeks to “capture,” observation. But the nature of that observation, allowed its subjectivity, can prove as elusive as it is rich.

That is to ask, is there mystery as well as revelation in the painting of Steve Shriver and Candice Gawne? What is left unseen but still sensed? The two painters are about as far apart stylistically and spiritually as two artists can get (at least within the context of two-dimensional representation). Their modes of observation are polar opposites, Gawne’s a register of the seen-world, a voyage through space and light, while Shriver’s is a fantastical rhapsody on the internal and the external — indeed, on the interplay of personhood and specific location with many stylizing, and culturally self-conscious, tropes.

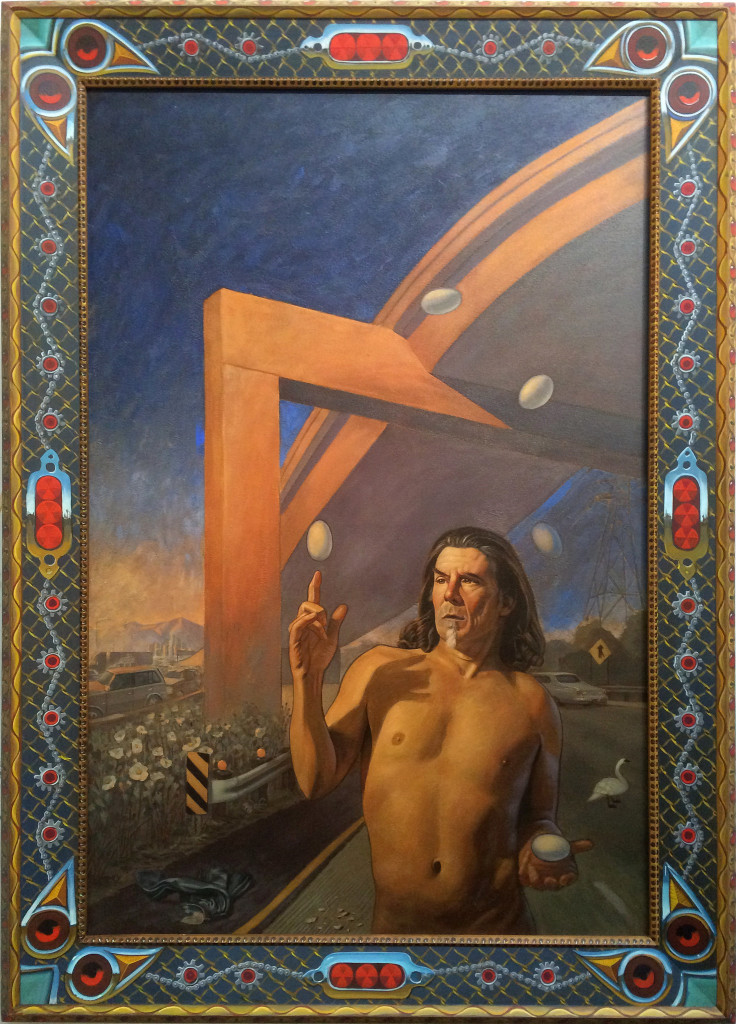

Shriver’s painting over the past two years all stems from a near-fatal accident he suffered while bicycling. On one level the elaborate, icon-like images — and the finely wrought frames and other accoutrements bedecking them — are a simple declaration of thanks to whatever force allowed Shriver not only to survive but to heal back into the artist he had been before. Except that, after such trauma, he couldn’t quite be the artist he was before. Pop irony was not appropriate for an extended (indeed ongoing) reflection on death, but the more exaggerated, yet more sincere, stylizations of lowbrow figuration were. In particular, the culture of the road, a motif central to the mythos of southern California as maintained by its inhabitants, figures in Shriver’s work as an imagined realm as well as a specific site (that site supposedly but not necessarily the location of the accident).

These images are at once violent and elegant, poised and calamitous, mocking and marveling. Having been there, Shriver knows how elaborate the complexities of personal disaster can be, in its moment no less than in its aftermath. Shriver’s is the PTSD not of the long-term sufferer, but of the ambushed, of the man all of a sudden knocked out of his comfortable life trajectory. These pictures are not exercises in self-pity. (If anything, more than a few of them are self-parodying.) They are not gore tests or macho poses of fury or nonchalance. They are declarations of a lesson learned and they brim with the humility of someone given his body and his life back. With a grandiosity born of relief and amazement they pay homage to the traditions of heraldry as well as to car customizing, mural painting as well as portrait and still life painting, political art as well as religious art. But, florid and dramatic as they can get, their energy seems to come from within and gather what’s out there — and to react from within a once-broken body to the mystery of life. Having observed his own dying, Shriver now observes his own living.

Gawne is awed less by such metaphysical apprehension than by its purely optical manifestation. She has become enthralled by light itself, its ability to hover seemingly in the eye, the contradictory conditions it sets up that at once shatter and build objects and surfaces, mass and movement. Gawne celebrates light — or, if you would, color — for its own sake the way Monet and Seurat and Balla did a century or more ago, as a radiant force that embraces, formulates, and pulverizes the observed world. Gawne regards the seen world not simply as the result of invisible sub-atomic particles in motion, in compliance with the concepts of quantum energy, but as the embodiment of that motion, a dynamic ongoing demonstration of the buzz at the heart of the universe, a buzz that is observable. Perhaps, her work posits, art’s purpose is to make the invisible visible — even as the eye admits its own myriad shortcomings.

Gawne brings the sub-observable universe to observable levels by giving the eye, that most inefficient of human organs, the opportunity to indulge itself. Whatever it wants to see amidst the flood of light, Gawne allows, even encourages, it to see. Rich in detail as her intimately scaled paintings are, they allow the eye to rest on blank passages as well as articulated, open fields of color as well as intricate chiaroscuro, stretches of abstraction containing, commingling, or separating figures and objects and portals and spaces so that we read her pictures as human and, at the same time, painterly events. Refraction is the steady state here: Gawne suspends her moments at a crucial point of observation, that point where the eye passes rapidly from dark to light or vice versa and shifts temporarily into a state of sun-white blindness or “visual purple.”

What Candice Gawne does looks hardly at all like what Steve Shriver does. Both paint, both reference the human figure, both fundamentally rely on concentrated observation to derive the images they depict. But, as noted, each does so to an end entirely foreign to the other. Gawne looks outward, Shriver in. And, notably, Gawne addresses space with light while Shriver addresses time — a fateful moment and its lasting effect — with graphic symbology. Still, both artists rely on deep, abiding observation, manifesting what they see and know with deep conviction, and without resort to the literal. That avoidance of the merely seen, and that conviction about the subjectivity of vision, create a mystery where our eyes can see what they normally don’t — or can’t.

Steve Shriver, gallerist Peggy Silvert Zask, Candice Gawne

- Peter Frank; images provided by SoLA