Powerful, poignant, and riveting, Jonas Kulikauskas’ I Often Forget, takes viewers through a heartbreaking and profound photographic exploration of the passage of time and of human relationships to it.

As curated by gallery director Mika Cho at Cal State LA’s Ronald H. Silverman, the work here absorbs and compels the viewer to enter an unfolding world both past and present, rendering those viewing it both accountable and stricken.

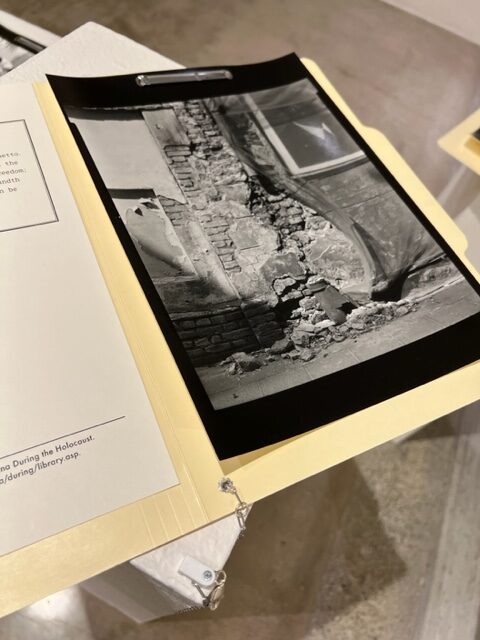

Together, Kulikauskas and Cho have assembled a deeply felt exhibition of both a photographic depiction of what was once the Vilnius Ghetto and a series of statements culled from the World War II-era that match their present-day settings, now modernized and/or hidden.

Along with the photographs and written history, there is a beautiful, fragile installation with white stones on the floor representing the loss of Jewish lives during the Holocaust, with a gauzy curtain obscuring a haunting image of the woods where some Vilnius Jewish ghetto inhabitants were hauled off and summarily executed. In another part of the gallery, a slide show unfolds, revealing many of the exhibition’s images projected in a subdued, hushed alcove.

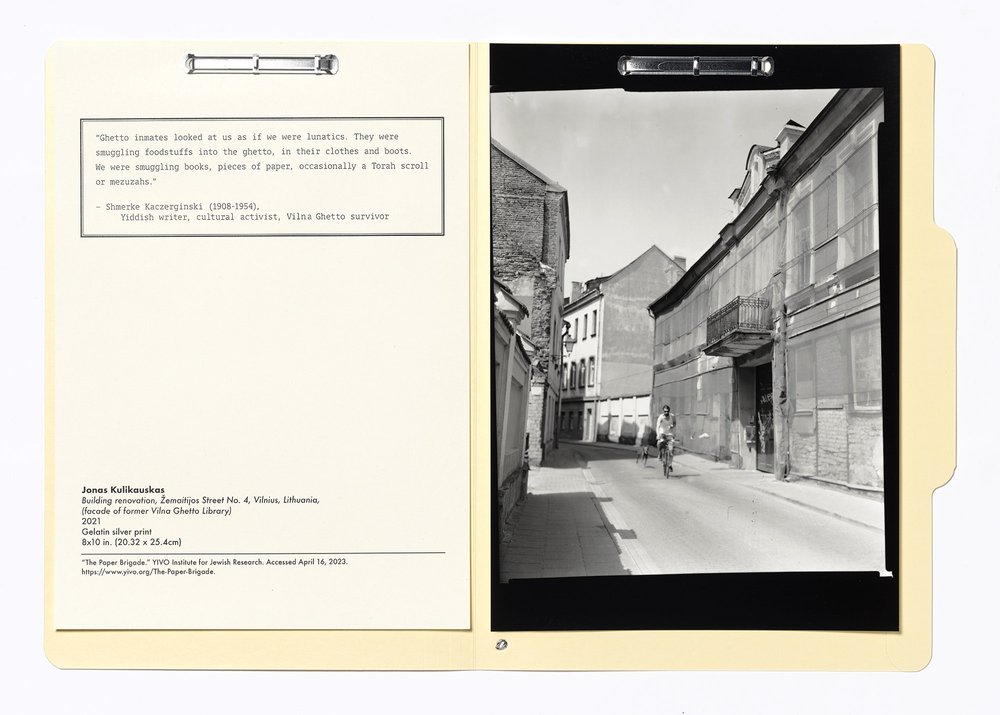

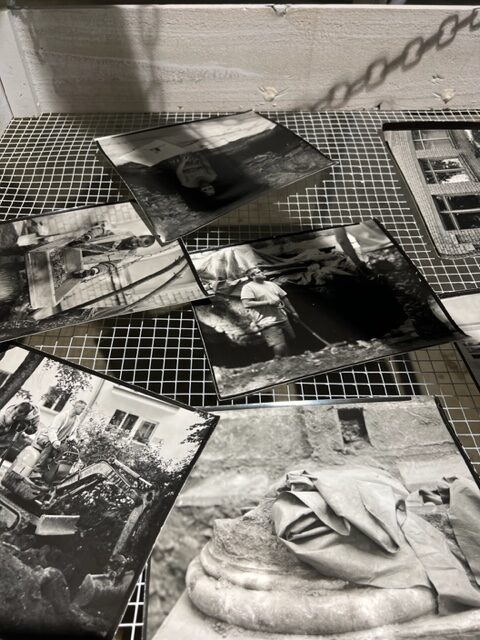

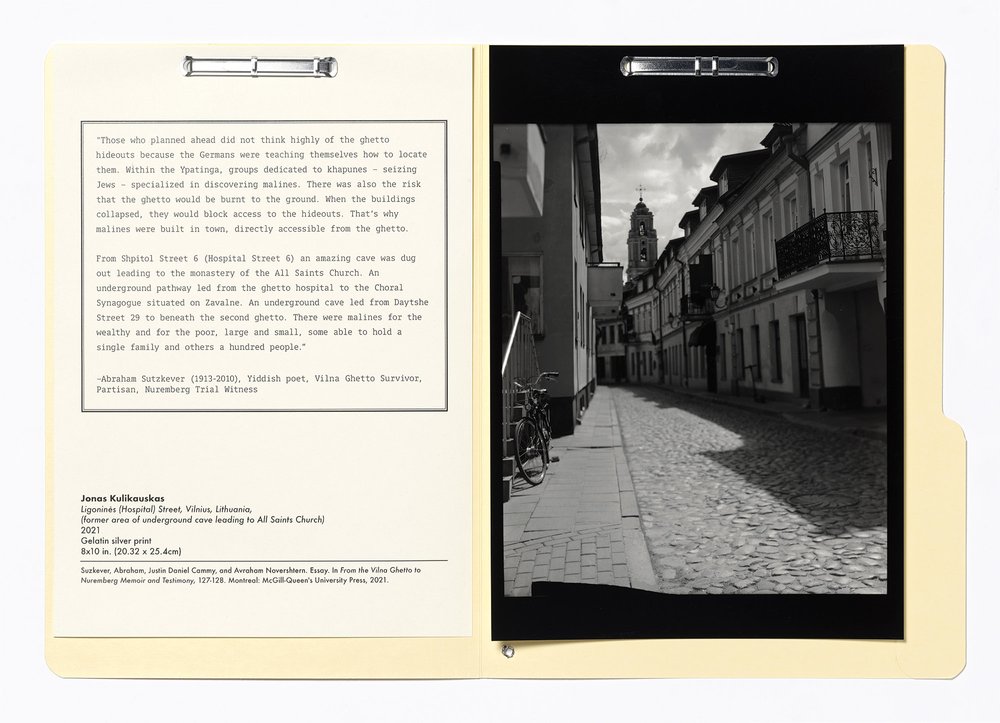

Some photographs are displayed laid out on the trays of sifters used as construction implements, another reminder of how today’s modern city is built on the bones of the past. Others are presented in folders on white pedestals and in files hung on the walls around the gallery space, allowing multiple viewers to study the photographs and the stories that accompany them.

In approach, this is a photographic exploration of the present layered upon the untold grief of the past. Kulikauskas used an 8×10” camera equipped with a World War II-period lens to capture life today in the former ghetto. Inspired by his Lithuanian heritage, the artist used his participation in the Fulbright Program and the additional support of the Puffin Foundation to travel to Lithuania, taking photographs and researching the traumatic history of the community.

His work is especially pertinent today with the disquieting rise of antisemitism and the horror of Holocaust deniers. He undertook his journey in 2021, and has, with the help of archeologist Dr. Jon Seligman, historian Dr. Saulius Sužiedelis, the Vilna Gaon Museum of Jewish History, and the Ronald H. Silverman Fine Arts Gallery, created a masterful exhibition worthy of reflection.

The passion of the artist’s commitment to his project can be felt in the bones of viewers, as he tells the brave, terrifying, and devastating researched stories of what happened when Vilnius, Lithuania’s capital and once called the “Jerusalem of the North,” was desecrated by the Nazi regime, its people effectively annihilated. Nearly a third of all residents were Jewish; 90% perished during the Holocaust.

This dark history has been largely hidden since that time. It has been literally built over physically in Vilnius, and few speak of that time. Even Kulikauskas’ parents did not speak of it, although they fled from Lithuania to Southern California, still speaking Lithuanian at home. The artist and his siblings attending a Lithuanian Catholic School on weekends, learning Lithuanian history and folk music but nothing about the massacre of the Jewish people in Vilnius.

While the Nazis were discussed, the Holocaust itself was not, something Kulikauskas, and now his son, who also attended the same cultural enrichment school, found deeply disturbing. This masterful exhibition is in great part a response to that lack of information.

In 2021, as a Fullbright scholar arriving in Vilnius to study the remaining Jewish Litvak community, Kulikauskas walked the streets of the ghetto. His guidebook, so to speak, was the historical diaries and testimonies about the life over 40,000 Lithuanian Jews led when trapped in the ghetto. Most were murdered by 1943.

Without Kulikauskas’ efforts, many of their words and experiences were well on their way to becoming lost. His photographs, despite their historic look, depict the present that has been busily swallowing these stories whole, subsumed behind shops and cafes and buildings now renovated into charming residences and tourist draws.

But in Kulikauskas’ work, the buried history of the Litvaks has been resurrected. And it is a stunning one. On September 6, 1941, the German and Lithuanian police began the roundup of the Jews of Vilnius into two quarters, separated by Vokiečių Street. A month later, the Nazis and Nazi collaborators had massacred most of the residents in the smaller of the two areas. According to Herman Kruk, who chronicled this period, 29,000 Jews were forced into the Vilna Ghetto which has previously housed just under 4,000 residents.

Ghetto inmates were forced to work for the Reich, and their lives were those of bare subsistence, while still fighting to preserve a meaningful life in the face of constant terror. Despite it all, they maintained a theater and a well-circulated library, while still taking part in both passive and active resistance to the Nazi regime. But before the war’s end, most were killed by their captors.

Kulikauskas’ work has not only exhumed their nearly forgotten memories, through it he has also offered a chance to memorialize their courage, their suffering, their hopes and dreams. It is no small feat, and I Often Forget not only provides an extraordinary exploration of this horrifying time in Lithuanian history, but does so with beautifully rendered images, deeply moving quotes and references, and with an eye on the future. He has preserved a grim, utterly horrible time and elevated the sacrifices, struggles, and meaning behind so many precious, lost lives.

Above, curator and gallery director Mika Cho

Both artistically and emotionally resonant, this is an exhibition that aches with longing, sorrow, and dread, and simply must be experienced.

The show ran at CSULA May 30 – July 7, 2023. Kulikauskas intends to travel the exhibition to other venues, and indeed, it deserves to be seen, felt, and experienced widely. There is a closing artist’s talk on Friday July 7th. If you can make it, please go.

- Genie Davis; photos: Genie Davis and provided by CSULA