Painting the Los Angeles neighborhoods of times past – specifically the 1920s and 1930s – artist Sarah Arnold creates lush, layered images that are as contemporary as their subject is historic.

The expression “to live in the present” is echoed in each of her works. She creates a vivid present-moment image of a rapidly changing landscape, one in which the architecture is historic, or perhaps already from the past. Just as shadows shift throughout the day, so does the look of the city, and she captures her own perception in the immediate.

Her thick, feathered brush strokes and rich textures form a mosaic-like detail; as layered as a collage, a tactile as if they were woven from fabric. Her lovely palette intimately reveals both light and color. Each landscape is depicted in an intensely measured, almost musical composition, as if each painted stroke were a rhythmic note played in a perfect tempo. She captures and preserves images of landmark structures with a graceful, flowing style, and infuses them with an inward glow, as if capturing them in a clear amber, in a resin that’s dipped in sunlight and shadow.

Each image appears as a moment frozen in time. That is not to say her images are either rigid or lost. Rather, the scenes are preserved – as befits an artist who also describes herself as an “avid architectural preservationist.” She describes the neighborhoods she captures as having diverse home styles and mature landscaping of lawns, gardens, and trees.

The eclectic nature of the communities she depicts include a sea of constant change – classic structures replaced by modern, and in danger of being eliminated by the drift of time and the urgency of construction.

Arnold says that she looks for neighborhoods teetering on the edge of irrevocable change, preserving through her art a singular moment in a community’s physical look, and its gestation of light and dark, tradition and change. Her work is not specifically representative of one home, one block, one roof; rather, she shapes a complex world, a special place that elevates a single moment in time, a single emotional moment – the Zen of home, a cocoon of comfort and a destination of the spirit. She depicts a rootedness that is too often pulled up, torn down, and obliterated in the ceaseless flow of urban life and popular landscapes. Each landscape is entirely different, though evoked in the same almost-dreamy style.

Her style is somewhat abstract, with a grounding in realism. We see the trees, buildings, flowers, sky but in an abstract/contemporary impressionist way. We get a sense of the neighborhood she’s revealing, whether through a unique tree or terrain, an architectural style or a quality to the rooftops catching the light of the sun.

With her painting “Wilmore City Jacarandas,” the darkest purples convey shadow and early morning light, they are lush and almost wild, a cascade of color and vibrating, lingering darkness.

The subject may be jacarandas again – her purple palettes are among the most compelling – but it is an entirely different view in the more muted late afternoon of “Purple Building with Jacaranda.”

Her view from “Kenneth Hahn Park” is all blues and greens in the foreground, intensely vivid; the long view of mid-Wilshire and Los Angeles is lost in a hazy blue grey, the nature both dominant and restricted.

“Terrace Park” gives us a long panoramic horizontal view of a street of houses and their trees, a larger blue building at the far right of the work, casting a shadow of dominance and change to come.

“Wilshire Vista,” is more urban, multiple-unit structures in groupings of quintessentially-LA architectural Spanish and deco styles and paler colors punctuated by a few in brick-red.

Using a plein-air technique, Arnold’s work, while perfect balanced, also conveys a sense of immediacy, an emotional presence impressed upon each scene. Fascinated with these Southern California neighborhoods, her many museum and gallery exhibitions include a lush current solo show at South Los Angeles Contemporary through October 31st.

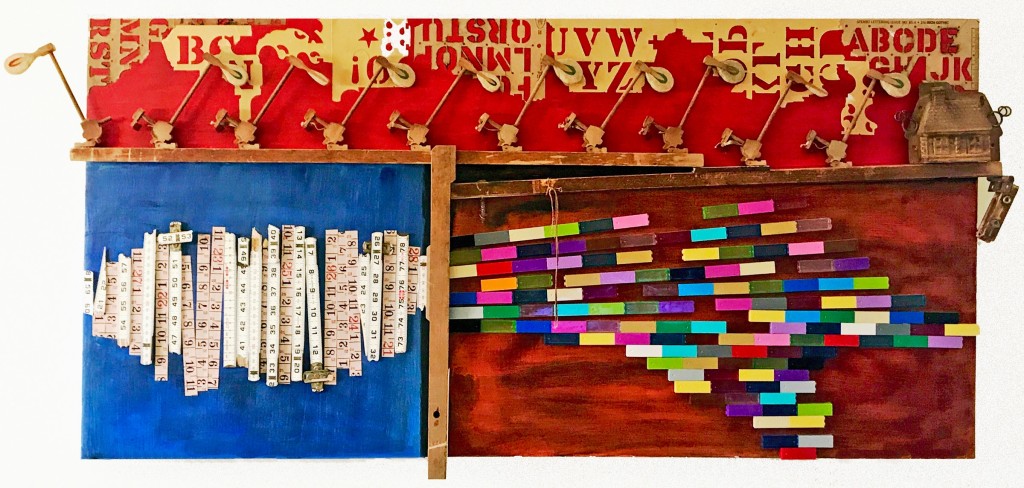

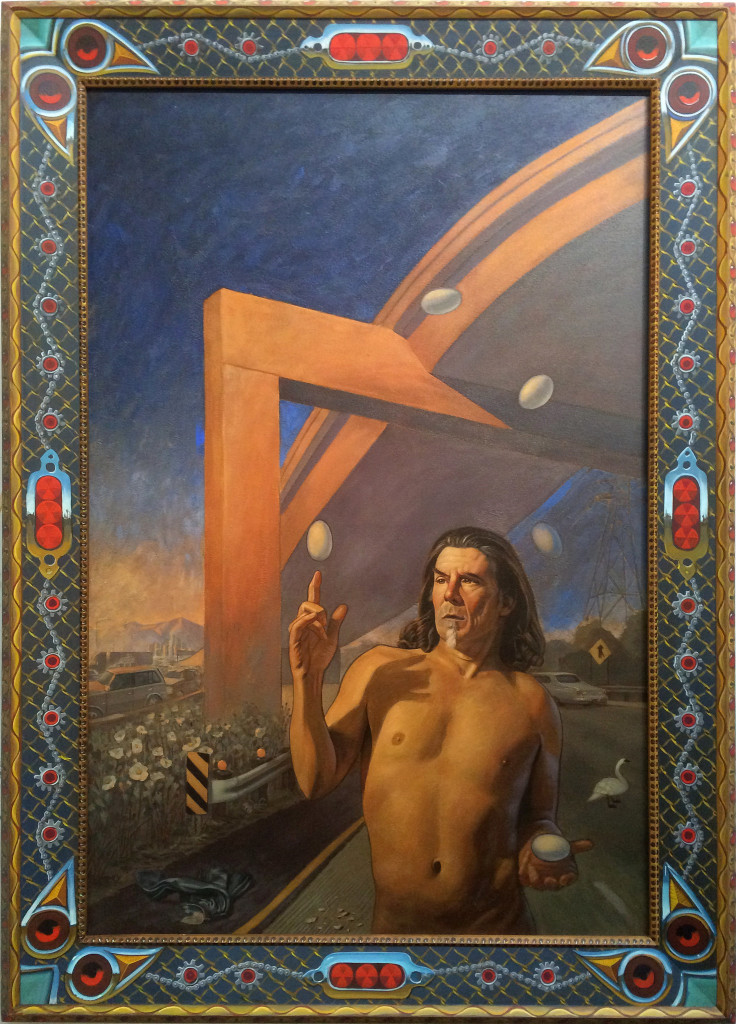

Arnold’s work is paired at SOLA with that of artists’ Charity Malin, Carmen Mardonez, and Kim Marra who comprise a wonderful group exhibition, Tactility. Arnold’s work deftly conveys similar themes to their beautiful show, those of memory and domesticity, and of creating a sense of place.

The place that Arnold creates is both dreamy and wondrous, poignant and poised to become memory. As an artist, she creates memories for the viewer that link emotion to place, and texture to landscape.

The gallery is open Thursday through Saturday, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., COVID-19 mask requirements are necessary; appointments are not, although can be requested for additional viewing times. SOLA is located at 3718 W. Slauson Avenue in South L.A.

- Genie Davis; photos provided by artist