According to artist Susan Lizotte, “A map is a lie, a beautiful lie.”

According to artist Susan Lizotte, “A map is a lie, a beautiful lie.”

Her description, which ties together her new body of work, resonates. We map territories, we map our feelings and emotions, we look for a map of the human heart. We map political gains and losses, trips taken and planned, future goals, financial foibles. As a human species, we are driven to make maps: perhaps it goes back to drawing routes with a stick in the mud, proclaiming or claiming the best hunting trails, the best berry patches.

How much of what we design, whether it is as exhaustive as Thomas Brothers map books of Southern California – remember those? Before Google maps and Waze were ubiquitious? – or as scant as a sketch on the back of a cocktail napkin, how much is empirically real? And can a map ever be ‘real?’

Sure, a rock is a rock, an island an island. But what it is named for, consigned to, defined by – that is an illusion. If there were no more cars on it, would the San Diego Freeway be a nameless artifact? If it floated from the land, unmoored, and sank to the bottom of the sea, what would we call it then? Would we simply pretend it didn’t exist?

An artist and curator, born in Los Angeles, Lizotte spent her childhood on both east and west coasts, and founded her own business as a designer of bespoke custom shirts and suits; precise creative work that has perhaps found a new form in her latest series of paintings.

Over the years, Lizotte has created gorgeous, evocative landscapes and skylines, abstract pieces that glow with hidden light, and her recent Mercury series, a powerful body of work that revolves around the discovered and undiscovered since Columbus “found” the New World.

His treasure hunt may have served as a stepping stone for the artist to move beyond the specifics of his annexation of a land already inhabited. For her, “Maps are one of the oldest ways of nonverbal communication and are a way to tell a story. Each map is a visual metaphor for identity, politics and propositions.”

Acknowledging that no map can be perfect through our own personal points of view and the very real physical distortion of our planet, she terms map-making a “subjective act of selection,” one which can be based on global navigation and imperialism.

Because of this subjectivity, Lizotte postulates that what is not shown on a map can be just as important as what is shown. “Above all, maps speak to emotion over reason and articulate our place in society and the world,” she notes. “For aren’t we always searching for who we really are?”

From a less weighty perspective, the artist adds “Visually, maps are really fun, a way to tell a story.”

She tells quite a potent one with her 12 x 12 series of oil on wood panels, New World I – VIII, which form a continuation of the work she began with her Mercury series, playing with the use of power and maps.

“The more people who decide what is included in the making of a map, the more distorted it will be, the less accurate. People decide together the things to be excluded and included.”

Seen together as one organic installation, these smaller works play off each other, they seem intense and immediate, both as visual forms and as maps.

As a viewer, I see a mix of islands, continents, bodies of water; the artist explains that she was led to the idea of creating a new world. “I could play with the ideas of the journey and what might be at each location,” she explains. “Visually the pieces could breathe if I introduced some space in each of them.”

These maps each stand repeated introspection as individual pieces, as well as being part of a comprehensive series, as she moves from a more realistic interpretation of map design in New World I to her most abstract in New World VIII.

Each piece has its own specific palette, pattern, and meaning. In New World IV, above, Lizotte says “I was playing around with the idea of Columbus, his ship hitting Hispaniola, the fact that the Santa Maria sunk on Christmas day offshore in the Caribbean. The thought I’m working with here is where they might’ve come in when they were hit, who was on the island, and then an image of the ocean lurking at the bottom of the canvas.”

The artist’s mention of the holidays stands out: there are red and green elements that remind the viewer of holiday colors, and land masses in the shape of wreathes or crescents. The waves in the right corner of the painting can be viewed as either isolated or creating the whole of the background, forming an ambiguous and fluid design that ties in well with the “what-ifs” of the subject matter. What if the ship had not sunk?

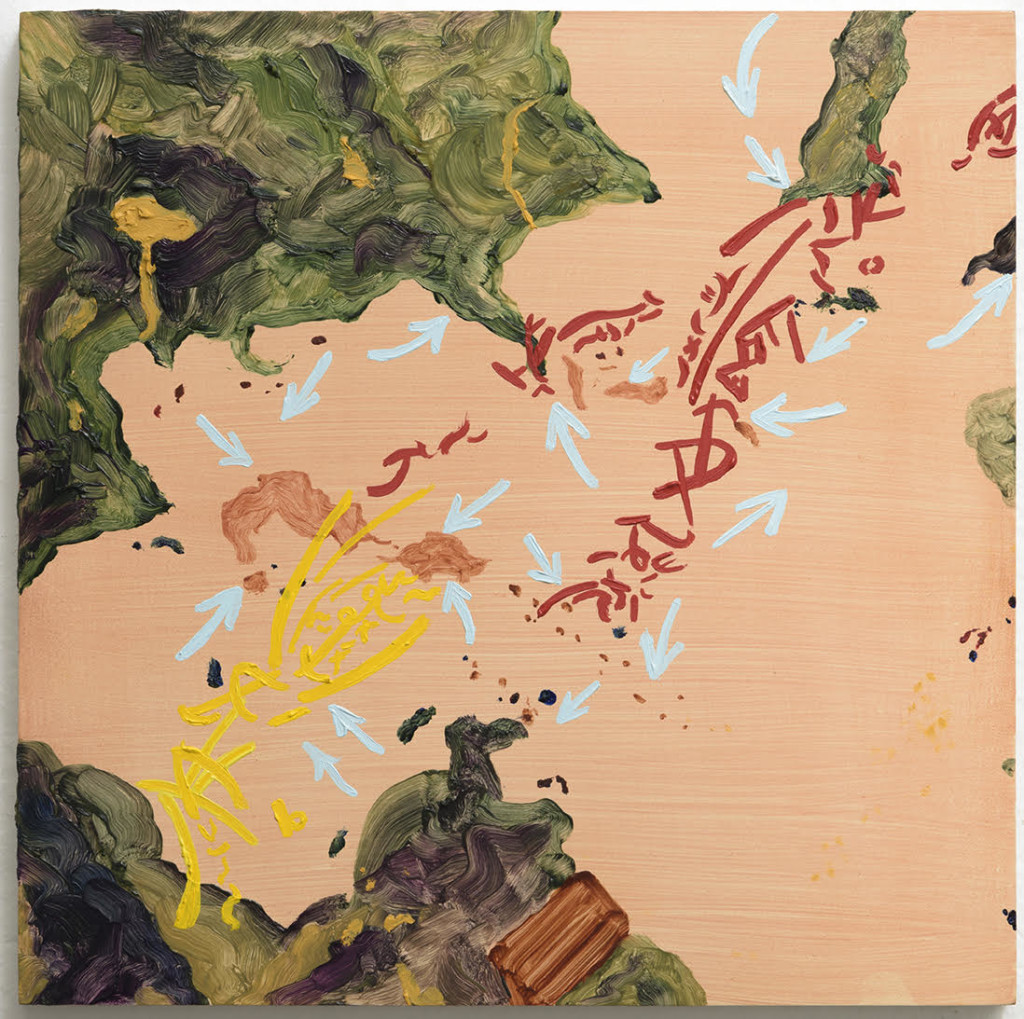

The decidedly pink palette of New World VII, above, reveals the concept of land masses grouped together yet separate. “When I was painting it, originally I’d held it in a completely different position to the way it is hung now, but there was no flow there,” she says. Changing the aspect of the wood panel, there is a very visual sensation of movement. “The yellow represents imperialism, the seeking of gold and treasure,” she relates. “The blue patterns evoke migration and motion, nothing specific.”

As a viewer, I see blue birds, pink sunset, and a pale blue water current pulsing over the solid forms. The thickness of the paint is enticing, in a piece that absolutely creates it’s own mythology of land, water, motion, and seeking.

“I layered the paint thick all summer. I was really excited that it was working, and it was humming,” the artist attests. “I wanted it to be wet on wet, flowing together, patterns, yet completely crisp, completely dry.”

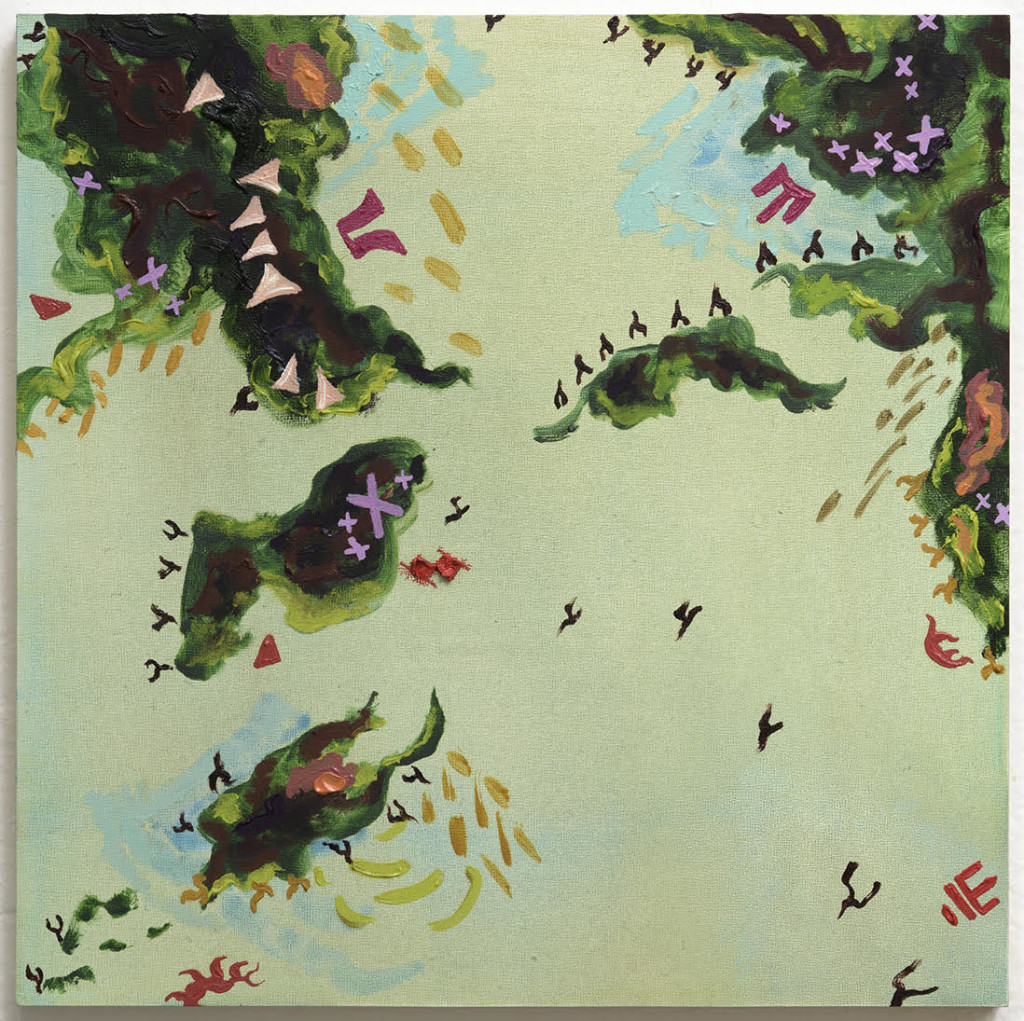

The first in her series, New World I, above, is markedly more specific in its design. “I really had the concept that I can paint a map, hold it in my hands, make up the topography, and see how that went,” she says. “Columbus and the imperialists took their journey, but I can represent that journey any way that I want. I was looking at old maps, the map keys from the Middle Ages, and not even knowing what they meant, making up my own symbols to conceptualize the journey,” she says.

With both New World I and II, above, you can tell that the background of each piece is clearly water. “It was interesting to me what happens if you take that away. To me, if it wasn’t blue or green, then the background changes and distorts the map, and you just go with that in terms of paint and point of view.”

With New World V, above, for example, the background is salmon, and the green topography wildly thick, as if mountains have sprung up on the canvas. Here, she includes blue arrows that she’d originally conceived of as water and currents, but could, she says, be “air or anything that moves.” Red patterns on the painting appear to have the rough configuration of Asian lettering. “Columbus was originally trying to reach the Far East, so certainly the red patterns could unconsciously represent that,” Lizotte laughs.

Whatever the journey you’re on, take a moment to savor Lizotte’s delicately beautiful and intimate trip. Maps themselves may very well be lies, but this artist’s paintings have the poignant and beautiful ring of truth, the truth of sunsets in forgotten places, treasure sought and found, greed and indecision, magic travels to distance lands and foreign thoughts. It is the stuff of memory and imagination, which is really all one can ask of any map.

These works and others will be on display in November and December, in three shows in the SoCal area, a part of MAS Attack 13, at the Torrance Art Museum in Torrance, Oil vs. Acrylic at the Las Laguna Art Gallery in Laguna Beach, and in Portraits, at the Beyond The Lines Gallery in Santa Monica’s Bergamont Station. Come December, she’ll be exhibiting with BG Gallery at Spectrum-Miami Art Fair, as part of Art Basel.

- Genie Davis; Photos: Jack Burke and provided by the artist